David Kenny is a professor of law and a fellow at Trinity College Dublin.

Peter McCarthy is a PhD candidate at the School of Law, Trinity College Dublin.

It is well known that Roman Catholicism played a central role in Ireland’s colonial and independence eras. Various formal legal disabilities on and discriminations against Roman Catholics under the Penal Laws were seen as a major source of British colonial oppression in Ireland. These laws were in force for a long time, and their longevity and impact distinguish the experience of Irish Catholics from many of their European co-religionists [1]. The divisions between Catholic Ireland and Protestant Great Britain were entrenched by reference to religious belief and status, and religious liberation was therefore a major part of movements opposing British rule in Ireland. Catholicism became the “central characteristic of Irish nationalism” [2] and the primary way by which to distinguish the colonizer from the colonized. The population of the Irish state was, at the time of its independence in 1922, more than 90% Roman Catholic, while Catholics were a small minority of the population of the United Kingdom.

It is well known that Roman Catholicism played a central role in Ireland’s colonial and independence eras. Various formal legal disabilities on and discriminations against Roman Catholics under the Penal Laws were seen as a major source of British colonial oppression in Ireland. These laws were in force for a long time, and their longevity and impact distinguish the experience of Irish Catholics from many of their European co-religionists [1]. The divisions between Catholic Ireland and Protestant Great Britain were entrenched by reference to religious belief and status, and religious liberation was therefore a major part of movements opposing British rule in Ireland. Catholicism became the “central characteristic of Irish nationalism” [2] and the primary way by which to distinguish the colonizer from the colonized. The population of the Irish state was, at the time of its independence in 1922, more than 90% Roman Catholic, while Catholics were a small minority of the population of the United Kingdom.

It is unsurprising, then, that when a strong Irish nationalist movement formed in the early twentieth century, Catholic identity would be a cornerstone of its aspirational, post-colonial self-image [3]. This is far from the only element of this identity—such identities are plural and complex—but is a major part of it. (Another crucial, related aspect—the status of Northern Ireland and the question of unification—is too great to be considered in the space available to us here and must await another occasion.) When the (mostly [4]) independent Irish Free State was formed in 1922, the extent to which “Irishness” and Catholicism were synonymous became apparent, particularly in the process by which Catholic social teaching would be reflected in its early legislative agenda.

The Religiously Motivated Laws of the Early Irish State

The 1922 Constitution was limited in what it could provide because of it being dictated in some respects by Ireland’s peace treaty with Britain and requiring broad approval from Britain. Therefore, it did not reflect in its text a confessional religious identity. However, in the words of leading Irish constitutional scholar (and now Supreme Court judge) Gerard Hogan, Irish politicians in the early years of the state “incorporated much of the Catholic moral code into the law of the land” [5]. The independent Irish state reflected in law the clerical obsession with moral purity, as understood through a distinctively Irish Catholic lens that had, amongst other things, a preoccupation with sexual morality [6]. A suite of legislative provisions was enacted to safeguard the body politic from themselves and the morally corrosive temptations coming from within and from their anglophone contemporaries [7]. The Censorship of Films Act of 1923 established a film censor with the remit of addressing films ‘unfit for general exhibition’ if deemed “indecent, obscene or blasphemous” or “subversive of public morality.”

The Censorship of Publications Act of 1929 allowed for the banning of indecent or obscene books, with the first chair of the relevant board being a Catholic priest. The character and attitude of Irish censorship in this era is summed up by Peter Martin:

Ireland was an oasis of virtue amid a sea of modernist depravity. . . . [E]ven when placed in the context of other liberal democracies, Irish censorship was notable for its harshness . . . . Underlying the existence of the censorship was the assumption that Ireland could not rely on other nations for its moral standards, especially not on Britain or America [8].

Similarly, following the teaching of the Church on artificial contraception as articulated in the papal encyclical Casti connubii, the Irish state banned the sale of contraceptives with the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1935, which stated, “It shall not be lawful for any person to sell, or expose, offer, advertise, or keep for sale or to import or attempt to import into Saorstát Eireann for sale, any contraceptive.” The censorship regime also made it an offence to publish material advocating contraception and birth control.

Clara Fischer draws attention to the particular focus on women in this construction of national identity in post-colonial state-building:

Underpinning the construction of Ireland’s newly emergent nation-state was a national imaginary that needed to clearly differentiate Irish identity from British identity . . . through recourse to the themes of purity, chastity, and virtue. The corollary of each of these, impurity, licentiousness, and vice, were attributed to the morally corrupt former colonizer . . . . [T]he moral purity at stake in the project of Irish identity formation was essentially a sexual purity enacted and problematized through women’s bodies [9].

Relatedly, a suite of measures controlled the social lives of the people, again drawing on Catholic ideas about virtue and vice. The Intoxicating Liquor Acts of 1924 and 1927 reduced the opening hours and number of public houses in Ireland. The Public Dance Halls Act of 1935 tried to tame the supposed evils of dance halls by requiring licences granted by district court judges.

Divorce had previously been possible in Ireland by way of private act of Parliament. In 1925, the standing orders of the Dáil (the lower house of the Irish legislature) were changed to disallow such bills, with the effect of banning divorce outright. W.T. Cosgrave, president of the Executive Council, said,

I have no doubt but that . . . the majority of people in this country regard the bond of marriage as a sacramental bond which is incapable of being dissolved. I personally hold this view. I consider that the whole fabric of our social organisation is based upon the sanctity of the marriage bond . . . [10].

Constitutionalising Religious Identity

Many other aspects of this Catholic identity were constitutionalised when a new constitution was enacted in 1937. Freed from limitations imposed by the British powers in 1922, the 1937 Constitution had many rhetorical acknowledgments of this identity. It begins,

In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, . . . Humbly acknowledging all our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial.

More practically, it introduced a constitutional bar on divorce. Its rights provisions, especially the property and family provisions, were heavily inspired by Catholic social thought [11]. Blasphemy was made a constitutional crime (albeit an unusable one) [12].

There were, however, limits to the Constitution’s embrace of a religious identity. Catholicism was afforded a “special position” in Article 44.1.2 ͦ , due to its status as the religion of the majority of people. This, however, was a recognition of sociological fact and not an establishment of a state religion. Such an establishment was prohibited, as was any religious discrimination, and free practice was guaranteed to all religions [13].

A Changing Ethos

We can say, from our current vantage point, that this confessional ethos gradually gave way to something amounting to a post-Catholic, pluralist, and liberal democratic ethos. There was a slow, gradual shift in this ethos in the decades after the Constitution was passed and then a much more precipitous change in recent decades.

Change came in part from the courts adopting a more liberal democratic interpretive frame in interpreting the Constitution, particularly constitutional rights, in many ways severing the religious origins of these provisions. Most famously, the Supreme Court in 1973 invalidated the prohibition of contraception for married couples by reference to constitutional privacy rights [14]. Supreme Court Judge Brian Walsh said the Constitution in its provisions was “acknowledging the fact that while we are a religious people we also live in a pluralist society from the religious point of view.”

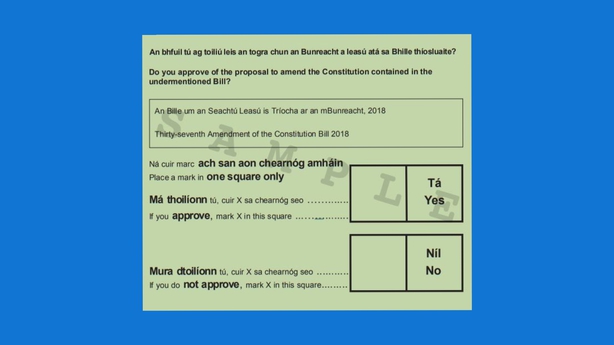

Even more significant was the composite effect of constitutional change referendums that changed the confessional feel of the Irish Constitution. An early change was the removal of the “special position” of the Catholic Church in the 1970s, as a gesture of rapprochement with protestants in Northern Ireland. In the 1990s, the constitutional bar on divorce was removed. In the past decade, same-sex marriage was provided for; the constitutional crime of blasphemy was repealed; and the regulation of terminations of pregnancy was provided for, removing a constitutional bar.

Following these changes, it is clear that the religious constitutional identity of the early Irish state has been substantially augmented. Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, in a speech given upon passage of the 2018 abortion referendum, echoed the rhetorical flourishes of the generation of Irish revolutionaries and state-builders in proclaiming that “[t]oday, we have a modern constitution for a modern people.” The factors that brought about these changes are far too complex to canvas well here, but changing attitudes to the social role of religion, and a diminution in the perceived need to markedly distinguish Ireland from Britain, have played a significant role.

Conclusion: Moving Past a Post-colonial Religious Identity

The early years of Irish independence are an archetypal example of a sort of post-colonial inversion, wherein the characteristics that served as identic justifications of suppression are inverted and centralised as identic traits that justify national independence. This inversion also serves to demote or marginalise identic/cultural traits of the former coloniser. Religion, sometimes a major point of differentiation between colonised and coloniser, can serve as a locus of inversion.

In the Irish case, this placed Catholicism, and the various cultural forces associated with it, in a hugely dominant position, while construing as alien or harmful anything supposedly too associated with “British” or “English” culture. The early legislative agenda of the Irish state bolstered and embedded this inversion, as Catholic social norms were woven into the legislative fabric of the state, along with the expectation that this would be the norm.

This trend continued for many decades, but a century later, such provisions have mostly been extricated, and Ireland’s constitutional identity is no longer predominantly defined by the attempt to contrast a colonial past. Catholicism may also have been seen as a stabilising and uniting force during an early and challenging stage of state building, in a polity having just experienced war for independence and an ensuing civil war. As time passed, the constitutional identity of post-colonial Ireland underwent a process whereby confessional binaries, so vital in conceptualizing the Irish state as expressed in its legal architecture, have been subverted.

References:

[1] R.E. Burns, The Irish Penal Code and Some of Its Historians, 21(1) Rev. Pol. 276 (1959).

[2] Dermot Keogh, Church, State and Society, in De Valera’s Constitution and Ours 105 (Brian Farrell ed., Gill & Macmillan 1998).

[3] Ireland does not share all the typical traits of a post-colonial state but does share many of them. For a compelling argument that it should be considered in such a light, see Bill Rolston’s Democratic Disruption: Ireland’s Colonial Hangover, London Sch. Econ. & Pol. Sci. Ctr. for Women, Peace & Security (5 July 2019). See also M.S. Kumar & L.A. Scanlon, Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity, 109(1) Annals Ass’n Am. Geographers 202 (2019).

[4] There were limitations on Ireland’s independence under this settlement, including notional legislative override in Westminster, appeal to the high court of the British Empire for some legal matters, and the monarch remaining Ireland’s official head of state. See Laura Cahillane, Drafting the Free State Constitution (Manchester Univ. Press 2016).

[5] G.W. Hogan, Law and Religion: Church-State Relations in Ireland from Independence to the Present Day, 35 Am. J. Comp. L. 47, 51 (1987).

[6] J.H. Whyte, Church & State in Modern Ireland 1923–1970, at 24–31 (Gill & Macmillan 1971).

[7] Id. at 36–49.

[8] Peter Martin, Irish Censorship in Context, 96(379) Studies: Irish Q. Rev. 261, 262–63 (2006).

[9] Clara Fischer, Gender, Nation, and the Politics of Shame: Magdalen Laundries and the Institutionalization of Feminine Transgression in Modern Ireland, 41(4) Signs: J. Women Culture & Soc’y 821 (2016).

[10] 10(2) Dáil Éireann Debate, at col. 158 (11 Feb. 1925).

[11] Dermot Keogh & Andrew McCarthy, The Making of the Irish Constitution 1937, at 111 et seq. (Cork Univ. Press 2007).

[12] No public prosecutions for blasphemy were ever brought, and in Corway v. Independent Newspapers (Ireland) Ltd. [1999] IESC 5, the Irish Supreme Court found that there was no actionable offence of blasphemy in Ireland, as the common law offence applied only to the faith of an established protestant Church that no longer existed in Ireland. A later Act passed a modern blasphemy offence to comply with the constitutional requirement for this to be a crime, but it was perhaps designed to be unenforceable in practice and was never used before the crime was removed from the Constitution in 2018.

[13] See Const. of Ireland of 1937, art. 44. The various minority religious denominations extant in Ireland at the time were explicitly recognised in Article 44, which specifically acknowledged the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations.

[14] McGee v. Attorney General [1973] IR 284.