Brandon Reece Taylorian is an associate lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire (UK). The following is Part One of a two-part post.

Introduction

States have a clear interest in the religious activities of their citizens. This is evident in how authorities apply limitations through law on where, when, and how religious groups propagate their beliefs and gather for worship services.[1] A government equally has a legitimate interest in controlling the flow of goods into a country. However, customs regulations can also restrict imports of religious goods, which in turn restricts the right to freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) of religious communities. Moreover, customs officials in countries with a state religion or a ban on certain denominations are more likely to target items unaligned with the religious or moral norms of the majority or privileged religion, as opposed to more generally targeting taxable items. Academic literature has granted insufficient attention to restriction of religion through customs channels, including to the question of which morality-related import restrictions constitute interference with FoRB.[2]

Part One of this two-part post draws on an array of data sources,[3] giving an overview of the range of state policies and practices that restrict importations of religious goods. It also provides an assessment of when customs regulations inappropriately limit FoRB, particularly when imposed in ways that demonstrate bias against certain religions. Part Two focuses on two 2020 European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) cases that show how states have applied their import regulations in practice, to the detriment of religious communities, and how the ECtHR determines a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights in the specific area of religious import restrictions

Religious Goods and International Standards

Customs authorities have a legitimate interest in stopping the importation of illegal drugs, weapons, and taxable items that smugglers are attempting to import without detection. However, in countries where the government has an equally vested interest in maintaining a religious hegemony or a hard secularization policy authorities are likely to interpret the importation of significant amounts of religious literature as a threat to national security or the public order, since the state religion or political ideology is often integrated with law and government in such states.[4] This is how many authoritarian states or states with official religions justify confiscating religious goods, either from individual travelers or from shipments made by religious organizations. The situation worsens when customs officials or state committees are tasked with reading religious materials to search either for “extremist” content, as defined by the law, or for publications affiliated with non-state religions. In these “content assessments,” officials actively regulate the religious content available to the public rather than simply look for items on which to impose import duties.

The term religious goods includes religious texts intended for personal use or propagation, statues, devotional cards, artwork, crosses and crucifixes, foodstuffs prepared according to religious law (e.g., halal and kosher foods), prayer beads, incense sticks, ceremonial objects like candles or altars, and items specific to certain denominations, like sacramental bread.[5] Without access to these items, individual and collective religious observance is hindered and the right to FoRB cannot be exercised in its fullest sense.

International standards protect the rights of religious communities, but these are not always precise as to the importation of religious goods. Customs regulations are so normalized that they can serve as a powerful tool to restrict religion under the guise of various commonly invoked justifications such as national security or the prevention of extremism. However, customs regulations contravene “the right to manifest one’s religion” “either individually or in community with others,” as protected under Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), when the state prohibits religious groups from importing goods essential to “worship, observance, practice and teaching.”

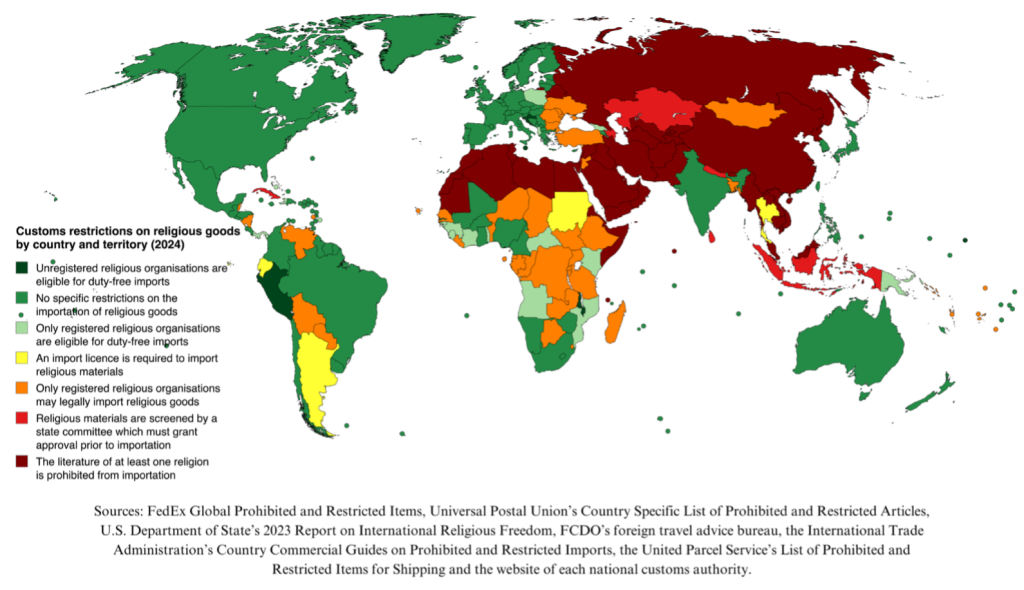

While some national constitutions such as India (Article 25) and Pakistan (Article 20) specify the right of citizens to propagate their religion, most do not include this provision. Instead, the right to propagate one’s religion is interpreted under the collective dimension of FoRB protections. With the lack of explicit right-to-propagate provisions comes a lack of international scrutiny of states that restrict the importation of religious goods, including religious literature intended for propagation.[6] Part of the issue is a lack of registration standards for religious organizations. In many states, registration is a mandatory requirement for religious organizations to legally import either religious goods generally or religious literature specifically. The map below provides an overview of the range of laws and policies regulating the importation of religious goods.

The map shows that customs regulations that interfere with FoRB are widespread and diverse but concentrated in North Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia. Regulations tend to be most severe in authoritarian states—especially those pursuing an ideology of hard secularization, such as the Central Asian republics and the atheist states in East Asia—or in Islamic states that enforce a strict interpretation of Sharia law.

Overview of Restrictive Customs Regulations

States where Sharia law is the basis of legislation have general laws prohibiting the importation of non-Islamic religious materials, but the extent to which such laws are enforced varies significantly.[7] For example, Bahrain, Brunei, Iran, Maldives, Mauritania, and Saudi Arabia are particularly stringent in enforcing customs regulations on non-Islamic religious goods. However, in practice, some customs officials may be more lenient than others, allowing into the country small amounts of non-Islamic religious materials. It can be difficult to anticipate how customs authorities will perceive a specific shipment or an individual’s attempt to bring into the country religious books, claiming they are for personal use. Many customs regulations in Islamic countries do not specify non-Islamic religious literature but instead prohibit literature contrary to Islam or otherwise offensive to Muslim culture. However, in many instances, this has been interpreted by customs officials to include non-Islamic religious literature or goods associated with religions other than Islam. Some stricter states, such as Saudi Arabia, do not allow any religious items without prior special approval by authorities.

Whether imported items constitute personal or public use is another crucial factor in whether they will pass through customs checks in some Islamic countries. For example, in Algeria, officials from four separate government ministries (i.e., Religious Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Commerce) must approve the importation of religious texts and items. As a general rule, Algerian officials tend to consider an “importation” to mean 20 or more items imported for public, rather than personal, use. A similar policy exists in Oman where large shipments of religious literature are likely to receive more government scrutiny and possibly be halted from importation, compared to smaller shipments of one or two publications brought in by individual travelers.

Broader political events can sometimes hinder religious freedom through heightened customs regulations. For example, the U.S. State Department’s “2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Lebanon” indicated that Lebanon’s “Jewish community faced difficulties importing material for religious rites” because “customs agents were reportedly wary of allowing imports . . . containing Hebrew script due to a national ban on trade of Israeli goods.” As a result, the Jewish Community Council decided to stop importing any religious materials into Lebanon in 2023.

The Role of Registration in Restrictive Customs Regulations

In other cases, the registered status of a religious organization determines whether its imports will pass through customs regulations. For example, in Bhutan, religious organizations must register with authorities before they may legally import any literature. Egypt, Kuwait, Moldova, Qatar, Romania, Tonga, and other states have similar laws. According to the United Nations’ Universal Postal Union, Bulgaria also restricts “religious materials of cults and organizations banned or unregistered.” Any state where registration is mandatory will require religious organizations to be registered before they may legally import religious goods, and in these states, imports of religious materials by individuals are more likely to arouse suspicion that the importer’s intended purpose is to proselytize.

However, in a further subset of states, registered status alone is not a guarantee of a group’s successful importation. For example, several states assign a government ministry or committee the task of reviewing religious materials before importation. In these countries, officials must read the religious content and decide––typically on undisclosed criteria––whether the literature may be imported. How these officials come to their decision could be based on several factors, including their familiarity with the religion associated with the literature, any preconceived notions or biases they hold against that religion, and the opinions of other “experts,” which in some states includes leaders of privileged denominations. The table below includes an inexhaustive list of countries that require a state regulatory body to review religious literature before importation.

For example, in Tajikistan, the state-controlled Committee on Religion, Regulation of Traditions, Celebrations, and Ceremonies (CRA) must review and approve all imports by registered religious organizations. The Tajik Code of Administrative Offenses stipulates that those caught attempting to import religious literature without the approval of the CRA will have their literature confiscated and will be fined, with the amount increasing into the equivalent of thousands of dollars, depending on whether the importer is an individual, a government official, or a legal entity and whether it is a repeat offense within a year. A similar schedule of fines for the improper importation of religious materials exists in the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. While these authoritarian states follow the Russian approach to the regulation of religious imports, their restrictions on religious literature may also be a domestic invention.

In addition, stringent customs regulations appear to impact religious communities in territories with limited or no recognition, such as the breakaway state Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria), which despite being internationally recognized as a part of Moldova, has operated with de facto independence since a brief military conflict in 1992. There authorities screen and have legal capacity to ban the import or export of printed religious materials. In the U.S. State Department’s “2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Moldova,” Jehovah’s Witnesses in Transnistria stated they were unable to import or distribute their literature as a consequence of being denied registration in that territory, a denial that mirrors Russia’s federal ban on the Witnesses since 2017. Similar dire circumstances for the freedoms of Witnesses persist in the partially recognized territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, where religious policy and restrictions also mirror those of Russia.

Russia itself adopts a restrictive importation policy by mandating that religious organizations qualify for registration as either a “local religious organization” or a “centralized religious organization” to legally import religious goods. Entities that qualify for registration only as a “religious group” (a category that holds a lower legal status than the other categories) have no legal right to import religious materials. In contrast, in Poland, the law specifically allows unregistered religious organizations to import religious literature without restriction.

Beyond interference with the right to manifest religion protected under Article 18 of the ICCPR, customs regulations sometimes impact more fundamental elements of religious observance. For example, in the U.S. State Department’s “2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Ecuador” Jewish and Muslim leaders in Ecuador raised concerns about onerous paperwork, customs regulations, and import tariffs that hinder their ability to import kosher and halal foods and beverages. According to the report, items imported with a religious purpose are not distinguished from commercial items under Ecuadorian law. This means they are taxed and subjected to the same scrutiny as commercial products despite being essential to daily religious observance. Given how import restrictions sometimes infringe the right to FoRB, perhaps special allowances might help reduce violations, or recognition for items imported for a purpose essential to religious observance.

Elsewhere, in officially communist states, even registered religious organizations are not free to import religious literature. In Cuba, for example, the Office of Religious Affairs must grant permission each time a registered religious group wishes to import its literature into the country. A similar regulation is set out in Decree 315 of Laotian law, which contains a blanket prohibition on the importation or exportation of any unapproved printed or electronic religious materials. The Ministry of Home Affairs in Laos has specific authority under the law to determine whether imported religious materials accurately reflect the beliefs of the group and comport with the values of Laos. According to the U.S. State Department’s “2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos,” members of the Baha’i community in Laos opted to produce and print their religious materials domestically to avoid stringent import regulations. In China and Vietnam, government officials must also review all religious literature before importation. Those attempting to smuggle Bibles into North Korea have had them confiscated at the border.

Criminalization of Unauthorized Importations

In other authoritarian countries, specific laws criminalize the improper importation of religious goods. For example, in Kazakhstan, attempting to import religious materials not previously approved by the state-controlled Committee for Religious Affairs is criminalized as an administrative offense with a 505,000 tenge (1100 USD) fine and a three-month suspension from conducting religious activities for registered groups. Meanwhile, Brunei has particularly stringent customs laws relative to religious literature, as all religious texts are listed as restricted items for import and require a government import permit before shipment. Importing literature associated with any religion the government considers “deviant”, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, Baha’i Faith, or Ahmadiyya, is a criminal offence, as is the importation of any publication deemed “objectionable”, which the law defines as describing, depicting, or expressing matters of religion in a manner likely to cause “feelings of enmity, hatred, ill will, or hostility.”

In countries where a denomination is banned, customs officials are obliged to look out for shipments that include publications by the banned organization. For example, in Singapore, the ban on Jehovah’s Witnesses extends to a prohibition on the importation of Witness literature. For offences involving the publication of material deemed objectionable, an individual may be subject to a fine under Singaporean law not exceeding 5000 SGD (3800 USD), imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months, or both. According to data from the United Parcel Service (UPS), Cambodia imposes a blanket prohibition on the importation of all religious materials and the authorities can impose penalties ranging from fines and confiscating goods for first offences to imprisonment for up to one year for repeat offences.

Duty-Free Imports and Customs Regulations in Democratic and Semi-democratic States

While registration tends to be used in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states to restrict the capability of religious groups to legally import goods, in many democratic states, gaining registered status is crucial to qualifying for waivers on customs tariffs and other import privileges. Such democratic states do not prohibit or otherwise restrict religious items—including materials intended for propagation—from importation and subsequent use by unregistered religious organizations and their members. Nevertheless, state discrimination in denying unregistered religious organizations import privileges, like waivers, presents a FoRB issue.

Albania, Barbados, The Bahamas, and Panama are among the countries where only registered religious organizations are eligible for duty-free imports. Meanwhile, Croatia, Malta, and Peru do not discriminate between religious organizations based on their registered status in granting duty-free imports. Most Western nations, as well as Brazil, India, Japan, and South Korea, have no specific import restrictions on religious goods. However, in Thailand, according to UPS, before importing “religious material,” the shipper must provide the actual purchase price or market value in the invoice, and shipments must be imported under the “Formalities Process,” which requires an import license from the Fine Arts Department.

Customs regulations contravene FoRB whenever they are applied with bias by officials or inhibit the ability of religious organizations to facilitate their members’ right to engage in “worship, observance, practice or teaching” by denying items necessary to perform those protected activities. Part Two of this blog post discusses two European Court of Human Rights cases that considered the application of customs regulations by states in ways that negatively affected the ability of religious communities to manifest their faith.

References:

[1] Roger Finke & Robert R. Martin, Ensuring Liberties: Understanding State Restrictions on Religious Freedoms, 53(4) J. for Sci. Study Religion 687 (2014).

[2] Mark Wu, Free Trade and the Protection of Public Morals: An Analysis of the Newly Emerging Public Morals Clause Doctrine, 33(1) Yale J. Int’l L. 215 (2008).

[3] For this article, I collated data on customs regulations from several sources, including the following:

- The restricted items section of the customs website of the country in question. However, some regulations can be vague, and while they often do not specify religious materials, this is what is restricted in practice.

- The U.S. Department of State’s annual “Report on International Religious Freedom.” This report not only provides information on customs regulations for religious goods by country, but it also features direct quotations collected by embassy officials from leaders of religious communities discussing the difficulties of importing religious goods.

- Detailed lists maintained by international couriers, including FedEx and UPS, of import prohibitions and restrictions by country. These provide additional corroboration as to how stringently customs regulations are enforced in practice. The Universal Postal Union (UPU), a specialized agency of the United Nations, regularly updates a similar “country specific list of prohibited and restricted articles” that provides some information on restricted religious materials.

- The British government’s foreign travel advice bureau run by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The bureau provides advice to British travelers on what they can and cannot take into a country, including religious items. The U.S. Department of State runs a similar bureau that provides information about restricted items, by country, to U.S. tourists traveling abroad.

- The International Trade Administration website. Run by the U.S. Department of Commerce, this website also has country-specific customs regulations but does not cover all countries.

[4] Songfeng Li, Freedom in Handcuffs: Religious Freedom in the Constitution of China, 35(1) J. L. & Religion 113 (2020).

[5] Jerry Z. Park & Joseph Baker, What Would Jesus Buy: American Consumption of Religious and Spiritual Material Goods, 46(4) J. for Sci. Study Religion 501 (2007).

[6] Falak Naaz, Freedom of Religion with Special Reference to the Right of Propagation, 5(1) Int’l J. Innovative Res. & Advanced Stud. 82 (2018).

[7] Raj Bhala & Shannon B. Keating, Diversity Within Unity: Import Laws of Islamic Countries on Haram (Forbidden) Products, 47(3) Int’l Law. 343 (2014).