Andrea Pin is full professor of comparative public law, University of Padua, and senior fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion, Emory University.

Syria, Constitution-Making, and Frustration in the Middle East and North Africa

The debate over Syria’s new constitution is the latest iteration of several efforts to pacify the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region while securing the rule of law and human rights. The twenty-first century is marked by an impressively long series of constitutional documents that have attempted to pursue these goals, with precarious or even disappointing results.

The geographic span of countries that have undergone such processes, often with international help, extends from Morocco to Afghanistan. In some cases, constitutional changes have resulted in amendments that left the preexisting elites in charge; on other occasions, new constitutions have marked dramatic regime changes.

Despite their differences, most of these processes did not deliver on their promises. Where constitutional changes aimed to do more than simply stabilize preexisting regimes, they failed to bring about the mixture of rule of law, rights, peace, and especially religious freedom that many were hoping for. This is particularly true in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, where religious and ethnic affiliations experienced a dramatic comeback on the political plane, causing turmoil and internecine wars, although the constitutional texts enacted in 2004 and 2005, respectively, were supposed to defuse tensions and assuage all religious and ethnic factions. In fact, these documents provided freedom for all and a neutral public sphere where individuals and groups would exchange opinions and deliberate outside of the groupthink that used to govern their lives. The new Western-backed regimes were supposed to give life to political and legal institutions that would be representative of each member of the entire national population. Religious freedom, political freedom, equal rights, and the rule of law were therefore the ingredients of these new constitutional mixtures that would treat people as individuals rather than as members of a specific ethnic or religious group.

Explanations for these constitutional failures have pointed a finger toward several factors, with special emphasis on a few: the lack of legitimation and the unwise unfolding of military interventions, poorly executed regime changes, the enduring influence of regional players, and an undeveloped political climate.

These factors have undeniably played a role and now also seem to be affecting the troubled Syrian constitutional transition. However, recent developments in Syria suggest further explanations for the uncertainties surrounding the new Syrian regime and the constitution-making process. The toppling of the Bashar Al Assad regime seems to have been mostly a domestic development; many were hoping for a regime change; regional players such as Iran now seem to be occupied with other tasks, at least for a while; and despite its fundamentalist pedigree, the new Syrian leadership seems to have embraced an inclusive approach to the constitution-making process.

Recent bloodshed in several areas of western and southern Syria, where government forces and militias skirmished with the Druze and Alawi minorities to which the Assad family belonged, suggest that important parts of Syrian society may not feel at ease with the new regime. In the eyes of such minorities, in late 2024 a brutal, oppressive undemocratic regime did not finally yield to democratic forces; rather, it yielded to a sectarian regime that is seeking retribution and the establishment of a new oppressive rule. They treat the post-Assad leadership as an overwhelmingly Sunni regime that is marshalling a new course that will sideline, discriminate against, and perhaps even persecute them. The democratic, egalitarian, nonsectarian dialectic that people expected would replace the previous iron-fist rule and that is also reflected in the draft of the Syrian Constitutional Declaration does not seem to have gained purchase among religious and ethnic minorities, some of whom have sought help from outside the country.

Of course, the constitutional clauses of the Syrian Declaration resemble many other constitutional documents in the region, which are often so ambiguous they may not be able to assuage disheartened minorities. Many texts place the respect of religious laws alongside clauses that promote religious freedom and equality, leaving to the interpreter the job of reconciling them. It is no surprise that citizens or observers may be skeptical about the outcome of such lofty provisions.

The issue of reconciling religious laws—and especially Sharia—with other constitutional precepts is certainly not a theoretical question and may lead to significantly different results in each jurisdiction. But an even more fundamental question seems to linger over the entire Middle East and North Africa, or at least large swaths of it: Is replacing sectarian regimes with religious-freedom– and rule-of-law–based regimes centered on individuals conducive to or counterproductive to domestic peace and stability in the region?

Misunderstanding Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

The United States has long exerted a centripetal force in modeling the protection of religious freedom around the world. Although many world constitutions and international law treaties do not subscribe to the U.S. Constitution’s strong First Amendment clauses, they hardly ignore the United States’ constitutional, political, and diplomatic emphasis on the importance of this right.

What is in U.S. books and national rhetoric is also found in real life. When I attend the religious rites of my church in the United States, I am always impressed by the outward-looking approach of any local parish I visit. Liturgical books do not just help me and anyone else attend and participate in the mass; they also take pains to explain the gestures of the assembly and of the priest, the significance of taking communion, etc., for those visiting the building or observing the mass out of curiosity. A leaflet is often also available for those who enter a Catholic church for the first time. It welcomes every visitor, illustrates the meaning of the mass, encourages attendees to actively engage in it, and explains why taking communion is reserved to Church members. It ends with encouragement to interested individuals to contact the priest or other local figure. In a nutshell, U.S. society—or at least U.S. Catholics—takes serious steps to ensure everyone can truly pursue a religious quest and eventually convert: this is an individual choice, which everyone may make freely.

In countries like mine, where the majority of the population shares the same faith—or repudiated it and any religious affiliation—there is little that resembles this approach. Leaflets still help Catholics follow the mass, but in most cases such leaflets do not contain the rites in their entirety—just the Sunday Bible readings and the assembly’s responses. This approach suggests that in the European environment religious conversion, or even curiosity, is not as common. There are of course exceptions and even renewed interests in religion—conversions to Catholicism have greatly intensified in places like France, for example—but the pattern emphasizes religious belonging over personal choice.

Still, the importance of belonging to an idiosyncratic religious community is not unknown in the United States. When I was visiting the Big Apple, a good friend of mine invited me to his church, the St. Vartan Armenian Cathedral of New York City, for a Sunday mass—so I could comply with my religious obligation of attending rites and experience the Armenian liturgy. However, he warned me that the liturgy is held in old Armenian, that it lasts a couple of hours, and that the attendees stand for the entire duration of the rites. These tips were helpful: I decided I would just take a peek at his beautiful church instead; I did not want to give my adolescent son additional excuses to skip mass.

Churches and religious groups that have a specific liturgical language and maintain their rites without aligning with the broader society seem to be particularly preoccupied with the preservation of their culture, mindset, and legacy. They may very much welcome conversions, but they must be aware that there are significantly high thresholds for others to overcome to understand the faith’s tenets and later embrace them.

The preservation and continuity of religious tradition across generations is particularly valued in the MENA region. One of the most eloquent constitutional articulations of this value is in the 1926 Lebanese Constitution, which is still in force and was among the earliest constitutions ever drafted after the collapse of the Ottoman empire and the beginning of the slow decolonization process. With its vibrant social life and extreme religious diversity composed of the historical minorities that found refuge on Mount Lebanon, where the Ottoman grip on power was more lenient, Lebanon has always cherished religious freedom. But its constitution seems to do much more than consider religious freedom important; it reflects a belief that protection and preservation of Lebanon’s religious communities are necessary for the survival of the country as a whole. Its Article 10 grants free education “as long as it does not disturb the public order, does not violate the morals, and does not touch the dignity of any religion or creed.” Education is a critical component of the survival of a religious community, and Article 10 of the Lebanese Constitution has been a constant reminder that education should not question the social, political, and cultural role of religions. In other words, for political and other purposes, Article 10 seems to prioritize religious stability over the freedom to convert. The survival of a religious community is particularly important for minorities such as the Druze, who do not accept conversions and, therefore, in freedom to convert see only risk that their community will shrink, with no chance that outsiders may join the group.

The need to preserve religious communities for political and institutional purposes radiates beyond the field of education. It is not just that ethnic and religious components are so ingrained in Lebanese society that Christians are very likely to vote for Christian candidates, Sunnis for Sunni-dominated political forces, and so on. Ethnic and religious threads are woven into the very fabric of the national political and constitutional tapestry: seats and public posts are allotted according to the religious affiliation of MPs and public employees, the balance of powers reflects the power dynamics among religious groups, and political negotiations tend to take place along religious lines.

In countries such as Lebanon, which are governed through what scholars call consociational democracies, political and legal institutions respond primarily to the groups that make up society, rather than to individuals. Through ethnic and religious apportionment of institutional seats, institutions themselves are supposed to hear, respect, and convey the concerns and priorities of each religious or ethnic faction. Institutions represent the people because they reflect each religious affiliation through the apportionment of seats, not because they are nonpartisan actors that are equally respectful of and distant from all religious groups. For minorities, the neutralization of religion in the political sphere and its replacement with a simple majority rule would look like losing any political leverage and giving all public powers to the largest religious group, which would certainly gain the majority of seats.

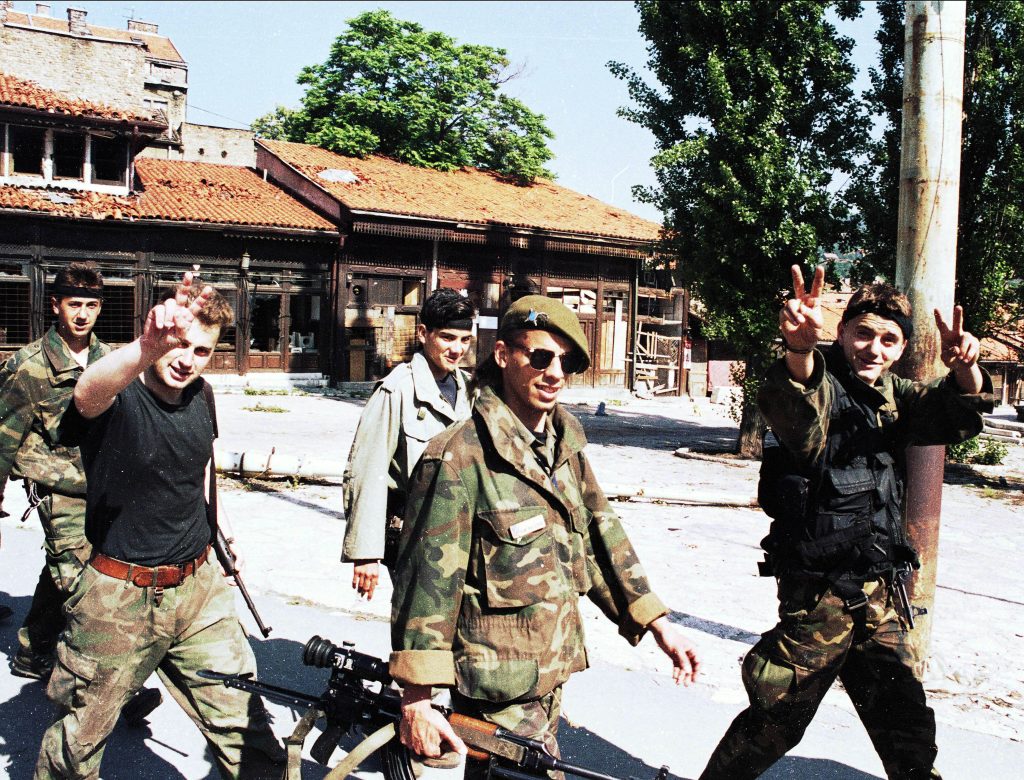

This logic is traceable throughout the MENA region but is especially visible in the Middle East, where countries are often much more ethnically and religiously diverse than in North Africa. When an international coalition eliminated Saddam Hussein’s elite and directed the transition to democratic rule, several Sunnis understood that the majoritarian Shia faction would take most of the seats in the Iraqi Parliament and sideline them. As a result, many Sunnis opposed the new course, and sizable portions of them joined the Islamic State, which claimed to defend Sunnis. Dynamics of this kind often propagate across borders, as disgruntled minorities find support from coreligionists in other countries, generating a domino effect that spins out of control. Think of the political triangulation between Shia Syria, Iran, and Yemeni Houthis before the collapse of the Assad regime, or the Israeli intervention in the Syrian region inhabited by the Druze minority. Religious ties may connect people who live thousands of miles away, such as when Arab Mujahideen solidarized and fought with Bosniaks against Orthodox Serbians during the Yugoslavian wars in the 1990s.

Seen from the vantage point of the individual-oriented religious freedom described above, many features of consociational systems look disappointing. In these scenarios, religious freedom is never an individual business; political and legal systems make religious affiliation and conversion a social and even political issue, with a series of ramifications that can gravely affect the free choice of each individual in matters touching on faith. One can also imagine the level of social pressure individuals perceive from extended family and acquaintances if they consider leaving their own denomination for another. If they change religion, they alter the balance of powers among religious groups. Even vindication of religious rights in court can be extremely problematic. Comparative constitutional law tends to view rights issues as a matter for tribunals. However, in deeply divided societies, where individuals find a place according to their religious or ethnic affiliation, claiming an individual right can pit plaintiffs against their group. This alienates them from the support and help of their group, leaving them alone and outside the social and political structures that govern the country. It is no surprise then that controversies are often solved through negotiations among groups rather than in judicial settings where individual claims are contrasted and interests are balanced by an impartial and independent judge.

Overcoming this sectarian logic and replacing it with a constitutional system that makes religious freedom a matter of individual choice and without legal or political significance is extremely difficult. In countries such as Afghanistan or Iraq, the commendable constitutional emphasis on religious freedom translated into fairly capacious religious freedom clauses and the prohibition of sectarian parties. These clauses were too optimistic. The political systems have never abandoned the religion- and ethnicity-centered political narratives—to the extent that, for the sake of domestic peace and stability, Iraq is still run through a de facto system of representation that reflects the nation’s ethnic and religious makeup. Although this may sound depressing to those who champion individual-oriented democracy, such a system provides peace to the extent that it assuages local minorities’ fears that state policies merely reflect the will and priorities of the Shia majority. In Afghanistan, the clash between the Taliban and democratic institutions concealed a struggle between pro-democracy and pro-West tribes that embraced the 2004 Constitution and groups that felt disenfranchised and soon endorsed the Taliban, facilitating their successful comeback.

The Syrian scenario does not appear too different from what happened elsewhere in the region. The Assad regime backed the Alawi and sidelined the Sunni; now the new regime says it is willing to implement a democratic regime, but minorities think that, in a predominantly Sunni country, democracy will merely lend a veneer of respectability to a Sunni-dominated legal and political environment that will discriminate against them.

The Price of Peace. Religious Belonging and Religious Conversion

Consociational systems are known to the West. For example, a solution of this kind surfaced in modern Belgium. In the late twentieth century, consociational agreements brokered peace in Bosnia and Northern Ireland, as they gave each of the prevailing religious communities an official status within national institutions and endowed them with veto powers on a series of critical issues.

Bosnian peace is still very fragile, and the encouragement of the European Court of Human Rights for Bosnia and Herzegovina to abandon its consociational mechanisms has actually been seen as a threat to the existing equilibrium. Northern Ireland seems more stable, although its flaws are also apparent. Following the 1998 Belfast Agreement, political players have too often resolved to veto each other’s political initiatives, stalling local political life. Such inflation of vetoes and immobilism are not just occasional bumps but likely natural consequences of consociational regimes that have been in full display for several decades now: Lebanon itself is notoriously plagued with inefficiency and lack of initiative. But the price of replacing the confessional constitutional system that was supposed to be temporary with a majority-based democratic rule may jeopardize the whole of Lebanese society. Consociational systems may start as a temporary settlement but then tend to solidify.

Since there seems to be a tradeoff between religious freedom and peace that is rooted in the tension between freedom and belonging, it would be better to acknowledge it.