Rakesh Naidoo is currently National Partnerships Manager–Ethnic at New Zealand Police, holding the rank of superintendent. He has worked with diverse communities for more than 30 years. The following is an edited summary of his remarks as a panelist at the ICLRS 29th Annual International Law and Religion Symposium, 4 October 2022.

Acknowledgment and Introduction

I begin by greeting you in the traditional language of the indigenous Maori people of New Zealand.

He honore / He kororia / Maungarongo ki te whenua / Whakaaro pai e / Ki nga tangata katoa

[Honour and glory to our Creator, peace throughout the land, and goodwill to all people.]

E Whare e tu nei / Tena Koe

[I acknowledge this esteemed house we are within.]

E nga mate hare atu ra

[I acknowledge those who have passed on.]

E Nga mana whenua tenei rohe / Tena koe

[I acknowledge the indigenous people of the land of this region.]

E te Rangatira Elizabeth Clark, tena koe

[I acknowledge esteemed Elizabeth Clark, program chair, and organizers.]

E nga mana e nga reo e nga aku rangatira ma e nga hou e wha / Kei te mihi kei te mihi kei te mihi

[I acknowledge the many leaders, representatives and chiefs present here and from across the country and world. Greetings to my esteemed fellow panelists and guests in attendance.]

No reira Tena koutou Tena koutou Tena Tatou Katoa

[My greetings to all of you.]

I share with you a New Zealand Police perspective on religions’ role in peacebuilding and start by stating a truth: Religion does have a key role in peacebuilding. In fact, if it were not for the New Zealand police’s strategic and long-lasting partnership with religious communities, we would not have been able to navigate and address some of the most pivotal issues that have occurred within New Zealand.

New Zealand’s Diversity

New Zealand is one of the most diverse countries in the world. We are a country of approximately 5 million people, consisting of more than 200 different ethnicities and people speaking more than 170 different languages. We are religiously diverse, with Christianity being our largest religion, but our fastest-growing religions are Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Islam. Ethnic communities—from Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, South America, and Eastern Europe—make up 20 percent of New Zealand’s population; within the next decade, those communities will comprise the second-largest population in New Zealand.

Maori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, have a strong foundation of Maori spirituality and are currently the country’s second-largest population. We are also home to the largest Pacific Island population in the world, outside of the Pacific, and they have a strong Christian foundation.

Incorporating Religion into Policing: A Reflection of the Community

Our country, while at the bottom of the earth, is still very much connected to and impacted by global and regional events, and its police organization must be cognizant of this environment. The New Zealand Police operates on a model created by the founding father of modern-day policing, Sir Robert Peel: that the police are the public, and the public are the police. We aim to police by consent and to have the trust and confidence of all. Our organization has a strong values-based foundation, focused on professionalism, respect, integrity, empathy, valuing diversity, and commitment to the Treaty of Waitangi (the country’s founding document, an agreement made between the British Crown and Maori chiefs). If these values aren’t embedded within a commonality, then we don’t have a strong foundation on which to leverage our work.

In short, policing a diverse community requires police to represent and reflect the community we serve. In 2003, the New Zealand Police made a strategic decision to address how the organization responds to changing demographics and how it can include and value all communities. This resulted in specific strategies like the ethnic strategy, the Maori strategy, and the Pacific strategy that targeted recruitment campaigns to increase diversity within the police. It also included a change in uniform protocols to incorporate the wearing of religious dress, such as the hijab and turbans, and the establishment of prayer rooms in police facilities. This approach differs from policing in other countries, where equality and uniformity may be more highly valued. The philosophy of the New Zealand Police is based on bringing your full self to work and not leaving anything at the door; you bring with you your beliefs, food, language, and dress, within the rule of law.

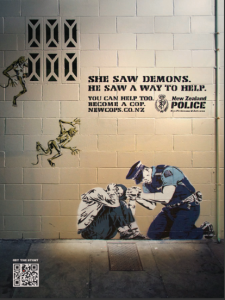

The New Zealand Police carried out a recruitment campaign featuring real-life stories of police officers. One of these involved a Christian police officer who responded to a call involving an individual who was suicidal and believed she was seeing demons. The person asked the officer to pray with her, and the officer did so. Drawing on common beliefs, the officer was able to engage with the individual, demonstrate the humanity and empathy needed to connect, and successfully resolve the incident. This story was incorporated into the recruitment campaign, which was particularly successful within our Pacific communities.

Policing a diverse community has also prompted us to appoint advisory boards to guide the police. The police implemented a prevention-first operating model that included religious representatives and interfaith representatives as wing patrons; the development of key resources, like A Practical Reference to Religious Diversity; the celebration of key religious events within police, from Diwali to Jewish holidays to Ramadan; and apps, training, and tools to guide police in engaging with the diverse religious communities of New Zealand.

In addition, police have implemented specific programs initiated by faith traditions. One is the Race Unity Speech Awards founded by the Bahá’í community. The New Zealand Police are now the primary sponsor of the Awards. When we started the sponsorship, we were questioned why we would do this when the program was founded by a religious institution. For us, the decision was not about who founded it but the outcome they sought to achieve.

Another program in which we are deeply involved is the Gandhi Nivas Early Intervention Family Harm program, which provides early intervention and prevention services for men identified as at risk of committing family harm in the home. The program has a phenomenal success rate: 60 percent of men who participate do not reoffend. It was founded by an Indian Hindu community that wanted to address, from a religious perspective, the family harm taking place within their community. That program now serves all communities of New Zealand.

Other programs include the Te Pae Oranga program, which addresses primary crime and victimization through a holistic community panel process; the Te Raranga Weave program, addressing hate crime; and the 3G4G Festival of Cultural Sharing education program, carried out with the Buddhist community, to name a few.

Police have also formalized relationships by signing key partnership memoranda of understanding—with organizations such as the Federation of Islamic Associations of New Zealand and Multicultural New Zealand—and supporting the activities of interfaith networks.

This investment by police is important because when key events have impacted New Zealand, this foundation built on partnerships, particularly with religious organizations, came to the fore to support a collaborative response to ensure our country could stay united and peaceful. I share some case studies to illustrate.

Case Studies: Religions’ Roles in Peacebuilding

2019 Christchurch Terrorist Attacks. On 15 March 2019, two consecutive mass shootings occurred in a terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch. The attacks were carried out by a lone gunman who entered both mosques during Friday prayer, murdering 51 people and injuring 40 others.

I was deployed to support and lead the community response on the ground in Christchurch. The aim was to work with leaders of New Zealand’s Muslim community to ensure that they, in and amongst this tragedy, were able to navigate a peaceful pathway forward. It was religious organizations that played a major role in the peaceful outcome; the National Interfaith Network ensured a peaceful response to the tragedy from communities across the country. Our country was on a knife’s edge, and if it weren’t for relationships already established, we would not have been able to successfully address such a tragic situation.

The Kashmir Files. More recently, we dealt with issues arising out of The Kashmir Files, a 2022 film about the genocide in the Kashmir region involving the Hindu community, which became highly politicized. We were able to work constructively with our Hindu and Muslim communities to ensure that a response in New Zealand allowed for freedom of expression and speech but ensured it was exercised in a dignified manner. Our chief censor was able to ensure the film’s release, while taking into account different people’s perspectives.

2011 Christchurch Earthquakes. A major earthquake occurred in Christchurch on 22 February 2011, affecting the entire Canterbury region in the South Island. It caused widespread damage across Christchurch, killing 185 people in New Zealand’s fifth-deadliest disaster. I supported and led the immediate community response for ethnic communities. Religious organizations played an important role in providing immediate disaster response with logistical, financial, social, welfare, and spiritual support. The Buddhist community in one suburb, for example, provided support for victims, translation of documents, and vegetarian meals for many who required them.

Covid Response. During the Covid pandemic, religious organizations played an important role in delivering food parcels. The New Zealand Central Sikh Association, for example, provided nearly 400,000 food parcels during the pandemic. Vaccination and testing sites, in some communities, were placed within religious organizations’ facilities; because these organizations had already earned public trust, the health sector was better able to engage with and work within these communities.

Refugee and Migrant Settlement. In addition to its government quota system, New Zealand refugee and immigration policy allows individuals to be sponsored into the country by religious organizations. Recently more than 1700 Afghan refugees have been brought to and resettled in New Zealand. This resettlement effort would not have been successful without the work and support of religious communities.

Misinformation and Disinformation. In a world filled with misinformation and disinformation, we find that New Zealand’s religious communities are playing an important role in promoting dialogue and fostering harmonious relationships. Interfaith networks and religious partnerships have come together with police to push back on radical ideologies and campaigns.

Conclusion

Religion’s role in peacebuilding is, therefore, multifaceted and covers a broad spectrum. It is essential that religion be included in the police’s efforts to maintain and build peace because religion is part of the community that police serve.

The windows of New Zealand’s Court of Appeal are emblazoned with a wonderful quote from Earl Warren, former Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court: “It is the spirit and not the form of the law that keeps justice alive.” In our policing and engaging with communities, it is key that we work with the spirit of the law, rather than just within the rules and regulations.

No reira tena koutou tena koutou tena tatou katoa

[I thank you all.]