Andrea Kupfer Schneider is Professor of Law and Director of the Kukin Program for Conflict Resolution at Cardozo School of Law. Schneider was the previous director of the nationally ranked dispute resolution (DR) program at Marquette University Law School in Wisconsin. In addition to overseeing the DR program, Schneider was the inaugural director of Marquette’s Institute for Women’s Leadership. Schneider has published numerous articles on negotiation, plea bargaining, negotiation pedagogy, ethics, gender, and international conflict. Her recent books include Discussions in Dispute Resolution: The Foundational Articles (edited with Hinshaw and Cole, winner of the 2022 CPR Book Award); Dispute Resolution: Beyond the Adversarial Model (with Menkel-Meadow, Love, and Moffitt); Negotiation: Processes for Problem-Solving (with Menkel-Meadow and Love); Mediation: Practice, Policy, and Ethics (with Menkel-Meadow and Love).

Schneider is a founding editor of Indisputably, the blog for ADR law faculty, and started the Dispute Resolution Works-in-Progress annual conferences in 2007. In 2016, she gave her first TEDx talk titled Women Don’t Negotiate and Other Similar Nonsense. She was named the 2017 recipient of the ABA Section of Dispute Resolution Award for Outstanding Scholarly Work, the highest scholarly award given by the ABA in the field of dispute resolution. Andrea Schneider was interviewed by Dmytro Vovk.

“If I Am Not for Me, Who Will Be for Me?”

You are a well-known alternative dispute resolution (ADR) academic and professional, but what is your experience in the intersection of religion and negotiation/mediation?

I was trained in both negotiation and mediation in law school and then started teaching them. And originally, it really didn’t occur to me that there was [any particular religious aspect to ADR], other than my own identity. (I was raised in Conservative Judaism.) But then I wrote one of my early articles on gender and negotiations, and what was striking to me is that my argumentation mirrored the Torah and Hillel: “If I am not for me, who will be for me? And when I am for myself alone, what am I?” (Pirkei Avot 1:14), or, in different words, if I’m only for myself, that’s a problem, but if I’m not for myself, who will stand up for me? This rhetorical structure of being assertive both on behalf of the community and on behalf of oneself was something that struck me early on.

Later in my career, there have been more specific opportunities to think about negotiation and mediation and religious communities in multiple aspects. The first is negotiation. My brother-in-law is a rabbi, and, in talking with him about his contracts and work, I gained some understanding about how things operated [in Jewish communities].

Then, more recently, I’ve done a lot of trainings for the Women’s Rabbinic Network, as well as for larger gatherings belonging mostly to Reformed Judaism, with a focus on rabbis’ and cantors’ work. At these events I have had many opportunities to look closely at issues of power and disempowerment, as well as gender and religion, that occur with clergy professionals and their congregations, and how negotiation and communal work interplay in this environment.

In mediation, I’ve done broader public policy mediations. Several years ago, I went to the Jewish Theological Seminary, which conducted a training for some mediators on the whole structure of how rabbis and cantors get hired. The organizers aimed, among other things, to create a cohort of mediators who understood how synagogues and clergy operate. Since then, I haven’t actually been called on to mediate these types of cases. But I really appreciate the expertise because this [training] gave me even greater knowledge about how recruitment, hiring, and movement occur in Conservative Judaism and in the Reformed Judaism movement as well.

Finally, as a lay leader, I’ve been very involved in my Jewish community. I find it very interesting to see from a Jewish communal perspective how contracts are negotiated—how recruitment, hiring, and firing happen in the Jewish communal world. It’s important that, while representing the broader Jewish community, nonprofit organizations themselves also follow the value system that they’re trying to promote. Concepts of equity and fairness—our treatment of Jewish communal workers, the professionals—are crucial and should match our religious values as well.

Why do religious communities need negotiation and mediation?

A short answer is that everybody needs negotiation and needs to develop their communication skills. We communicate on a regular basis to accomplish what we try to achieve, whether it’s our day-to-day existence or broader goals of the workplace. We communicate in every hallway conversation, email, or other form of interaction; these are parts of a pattern of communication and negotiation. There are professions that have the opportunity to be professionally trained in negotiation and mediation, like lawyers. There are also professions, however, that don’t have the opportunity to get trained, like clergy and, by the way, architects, doctors, and other high-end professionals. And we need those communication skills. While some people are naturally good at them or have been socialized, all of us could improve how we communicate.

In terms of mediation, clergy often find themselves in the middle—for example, in the middle of family. Think about a child who is getting Bar or Bat Mitzvah’d and a rabbi or a cantor negotiating with the parents over how they envision the ceremony, explaining, for example, how much Torah the child should learn or can learn before the ceremony. This is a mediation. Think about a rabbi who is in-between families and counseling, either when a family member is dying or right afterwards, to manage the family relationship between the spouse who may want [one thing] and the children or siblings [of the deceased] who may want [the complete opposite]. The rabbi may or may not have his or her own take on what should happen, but the role of a neutral person in managing those conversations is somewhere clergy often find themselves.

This makes mediation so important, let alone the more traditional negotiations/mediations we would imagine between different congregations as we evolved. Should women be able to read from the Torah? Should non-Jews be able to be on the Bimah when the Torah is out? These are the evolutions of congregations in the United States. In addition, congregants might have very strong opinions on whether rabbis should be officiating intermarriage or gay marriage and whether Sunday School should be two hours or three hours. For every single decision or interpretation of Torah, there could be clergy who have their own opinions and congregants [who have] equally strong opinions. Therefore, mediation and communication skills that a rabbi or a cantor should bring to the table to facilitate a conversation are critically important.

Finally, there are negotiation and advocacy skills for oneself. Clergy go into this field because they are deeply committed to the community and to the pursuit of their religion. Yet if these clergy are not happy in their day-to-day existence, if they don’t feel valued, if there are too many things on their plate, or if they feel underpaid or taken advantage of, they will leave or, at least, won’t be able to serve in the way that the community wants them to. (One may recall that the number of people being educated as rabbis is dropping.) There has to be some recognition of how important it is to manage individuals’ lives and meet their interests, some understanding that it’s a “give and take”: it’s not only the rabbi who is supposed to give and give and give to the community. The community needs to support the rabbi and the cantor. This perspective on communal life is no less significant.

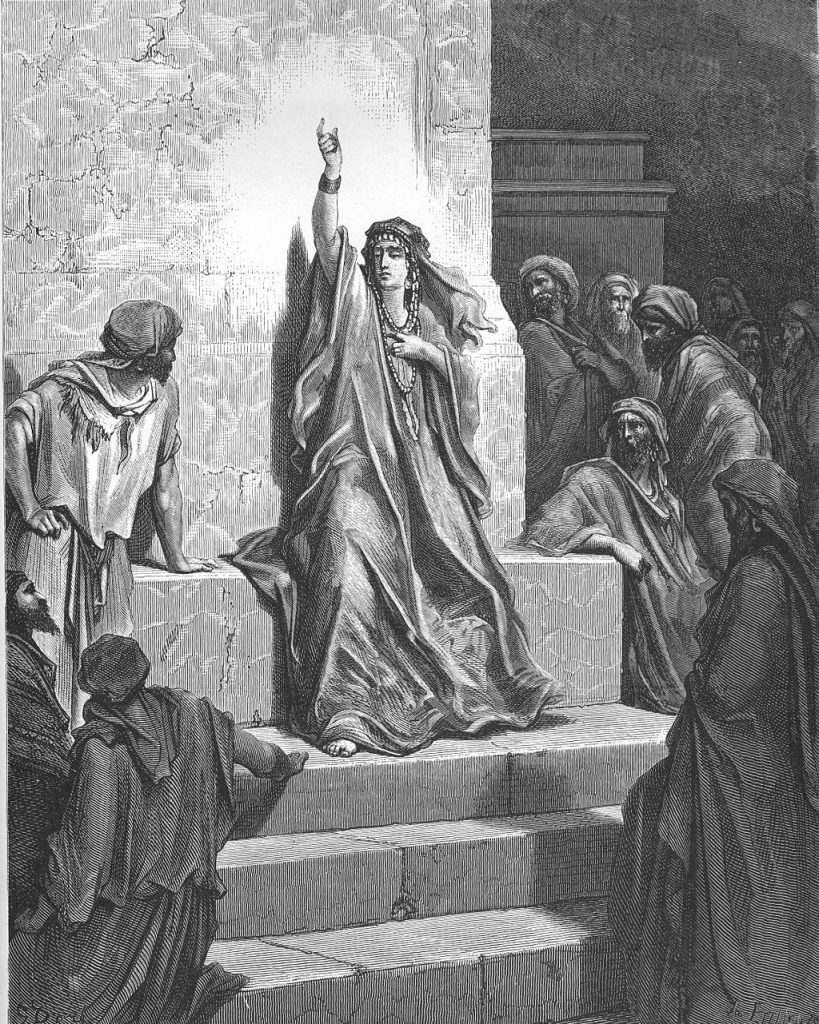

Also important is that most religious communities I’ve learned about, talked about, or talked with have the idea that disputes within the tribe are best handled through conversation or mediation; in many religions there’s a long-standing idea of a wise elder. One can find it in the Chinese or Hindu traditions and, obviously, in the Torah. King Solomon is often used as an example of classic arbitration. He sits as a judge deciding whether the baby shall live or be divided in half. Think also about Deborah as a judge: she sat under a tree, and people would come to her with problems. In these circumstances, she is much more viewed as a mediator or a wise elder than as a kind of Temple of Justice, “Thou shalt do this.” This is not to say that judging or an adversarial process isn’t valuable or needed sometimes. But the concept of trying to work things out—the concept of how we can resolve this dispute among ourselves peaceably, effectively, efficiently, and fairly—fits our religious tradition.

It’s obvious that your Jewish background might be helpful for conducting mediation or negotiation, or conducting training in mediation skills, within Jewish communities. But are there situations where your Jewish background—a feeling that you are part of this community—creates a challenge to you as a mediator or facilitator?

There are times where I have felt torn in terms of loyalty. Years ago, I found out in my Jewish community that there were women who were being paid less than they should have and less than the men were paid. Should I be pointing that out? On one hand, the budget needs to be balanced. If we pay more in salary, then there’s not as much money going to programming or the needy or supporting schools. On the other hand, how can we promote equity and justice if we are not just within our own home?

Another example that comes to my mind is parental leave. Many nonprofit organizations (not only Jewish organizations) have parental leave policies, which are appalling as far as I’m concerned (or have none at all). No doubt if you’re a tiny organization with only one professional hired, to lose this professional for three months is problematic. But still, you’ve got to walk the walk [and establish a fair parental leave policy]. These are times where I have felt torn. As a person in a position of fiscal responsibility, I know how tight the budget is. But I also think that ongoing injustice doesn’t serve a larger community. What kind of example are we setting if we’re not supporting parents with parental leave while we need more people in the Jewish community?

Another aspect of this problem I learned about, from talking to clergy while doing negotiation training, is a personal contradiction clergy might feel [between the goals of serving the community and meeting their own needs]. Again, they know the budget is tight. They didn’t go into this profession for the money; it’s also the value loop. (We hear this as academics as well, right? We don’t go into this field to become wealthy.) So they’ve made career choices, where it’s not about the money. Thus, their identity is conflicted. If you view yourself as, first of all, serving the community, then how can you ask for more money from the community? This is an internal conflict that I have often seen in clergy and Jewish communal professionals. Yet we should validate the importance of both things. Rabbis’ work is not about the money, but they still deserve and need a fair living wage.

Outsider versus Insider

There is a distinction between “outsider-neutral” and “insider-partial” models of mediation. What are their advantages and disadvantages of these approaches being applied to religious communities?

In fact, the insider model of mediation was historically first. If you look at past religious traditions—Confucian, Hindu, Native American, indigenous—it is the wise elder, who is inevitably an insider, who knows the community and the families and will have an opinion [on the dispute]. The advantage of the insider position for a mediator is, of course, that the insider has a sense of what’s going on. This person has a relevant background—knows the parties, the dispute, and the background layers—as often a dispute is not a simple “This is what it is”; it can be a symptom of long-standing differences. Then there are advantages afterwards because, whatever agreement is reached, the insider will have signed off—the insider may well have suggested it—and parties will comply. The insider model has value in ensuring that this is done: this is the way that we’ve agreed, and it will be carried out.

However, the flip side is that the advantages I’ve listed can also play as disadvantages. That’s why in legal communities you will see the model of an outsider neutral, where we don’t want people who come in pre-judging the parties, who have seen [the parties] since they were age three and have an opinion about their character or their family’s character. We don’t want mediators who have widespread knowledge of the family finances or lack of finances and who may have an opinion about how mediation should come out. The advantage of an insider who is able to suggest an outcome is a huge disadvantage if the insider is viewed as partial, biased, or unfair. This can make parties want an outsider who is either suggesting something based on completely different experiences or who doesn’t make suggestions at all and has the parties really mediate between themselves for the kind of solution that makes the most sense for them. The outsider-neutral model has more of a tradition than the insider-partial one of letting the parties come to their own solution. I haven’t studied religious communities per se, but in general, at least empirically, when parties come to an agreement themselves, they’re also pretty likely to carry it out, even if there is no insider to supervise it.

Finally, there is also a cultural aspect of the problem. For many cultures, the idea of the Western or legal model of the so-called outsider who is completely neutral seems crazy. Why would we trust somebody who doesn’t know us at all, doesn’t understand our traditions, doesn’t know anything about what’s important to us? Similarly, Westerners or Americans would consider an insider mediator as potentially biased. Overall, there is a long tradition of both models; they are both valuable, and they both have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Given that, would you agree that there are some types of disputes where the insider model works better and others where the outsider model works better? For example, it’s hard to imagine a complete outsider mediating who will read the Torah.

I agree. When clergy serve as the mediator, they often find themselves in the position of a classic insider: here’s what you know; here’s what the Torah says about how we observe, for example, the end of life; or here’s what scripture might suggest about inheritance. In this situation, the clergy can perform as a sort of neutral expert in these issues bringing their expertise to the table in addition to knowledge of the family and the dynamics and other things. This makes a lot of sense in terms of accessibility, timing, and importance to the family. Therefore, I do think that clergy should be trained in these skills and would benefit from such training. They’re going to find themselves in the middle of conflict, whether they want to or not. So it matters when clergy have the ability to take a step back, encourage parties to work on active listening, or help them reflect back to gain understanding. Overall, day-to-day mediations over Bar and Bat Mizvah, the officiation of weddings, and the determination of who can read from the Torah won’t be handed over. They fall within the purview of the synagogue. No community will hand this to an outsider.

On the other hand, there are some controversies where certain outside norms or standards are involved. (Think about salary disputes or standards understood in a certain way by communal organizations across the country.) It’s useful information for the parties. Often there’s a lawyer or a mediator—an outsider who can use or apply those criteria to the controversy. When the only one you have is an insider who is not aware of these norms or standards, you are missing some important, useful information in terms of helping people resolve the dispute.

“Her Salary Is an Add-on”

You have already touched on the gender aspect of religious communities’ life. Do you see any evolution of men’s and women’s roles and positions within the religious communities you have dealt with professionally?

I see some significant gender evolution in many fields—from women getting Bat Mitzvah’d and, in conjunction, reading from the Torah, to more leadership within synagogues and Jewish communal organizations. There is an entire growth [of women’s agency]. The interesting thing is that women’s integration into religious leadership is occurring everywhere across Jewish denominations but at different paces. At the same time, one may look at the assumptions about a woman’s salary as “secondary” salary; that’s the assumption that a woman doesn’t need as much because her husband is already a doctor or a lawyer: “Her salary is an add-on; it doesn’t need to be fair. We don’t have to pay a market standard that we’d have to pay to a man.” That used to be a message for a long time.

Think also about gendering professional roles. While there are more women in the Rabbinate, women are still more likely to be education directors, or work at schools or Jewish community centers, where the salary is less, by virtue of that role. One can look historically and say the education director has always been [underpaid]. Yes, the education director has always been a woman, and her salary has always been low. But this doesn’t make it fair.

We are now going through the second generation of pay equity. The first was the commitment not to pay a woman at any position less than you would pay a man at the same position. I think the vast majority of organizations are there or are getting there. I think, in terms of pay equity, the next piece is to look at professional roles themselves and how they’ve been gendered, as well workload (hours, responsibilities, etc.) versus the title. Still, sometimes we call somebody a janitor, and they are paid more than the cleaning lady, while they both do the exact same thing. So there’s definitely been significant progress, but there’s more to be done. Every part of Jewish tradition talks about equity and justice. We need to walk the walk.

Do you feel that, while requesting pay equity, women of faith experience tension between their request for greater equality and their religious identification, or do they think about and articulate this request as a part of their religious identification?

For some women it’s a conflict in terms of the fairness of asking for more. It’s not a conflict in terms of [the request contradicting] their religion. It’s more a contradiction, as I mentioned earlier, within the identity of “I went into this profession to serve my community,” and asking for more salary seems selfish. I think more women than men have been socialized to feel that asking for yourself is selfish. Again, this is changing. Every study says that, when men and women are trained, they negotiate at equal rates equally effectively. It’s not an inherent biological feature. It’s socialization (through parents, family, community, society in general) that imposes this understanding on women and some men. This is not just about clergy, by the way. This type of socialization is going on in various professions. Think about scientists who come to the profession with an understanding that “I’m here for the science. It’s not about me; it’s for the science,”and that negotiating on behalf of themselves is selfish and contradictory to their own self-identity.

I think it can help if you can view equity and justice as a part of your religious tradition and that advocating for yourself is, in fact, a part of ensuring that the institution you are with is equitable and walks the walk for everyone in the building. From empirical research we know that when people find negotiation on behalf of themselves as consistent with their self-view as professionals, they are more inclined to go into negotiation and are better at it. It’s especially important for people in leadership, either as community members or as high-end professionals. For sure, if they’re not asking for equity, entry-level people who have no power whatsoever will not do it as well. It’s very close to the role of tenured faculty in academia. In my previous institution, I never had parental leave; it was not a thing. As soon as I was done giving birth, I got on the committee to change the situation. I knew that I’d not be benefiting from it, but the next generation had to have parental leave as an option. Similarly, the clergy already in place need to be advocating for themselves and for the next generation so that it just becomes part of the DNA of our Jewish institutions.

Tips and Lessons

Are there any specific practical tips that would be helpful to facilitate negotiation/provide mediation within religious communities?

Despite my Jewish background and some knowledge of the Torah and Judaism I’ve gained over years, I am still an outsider in a community of people who have devoted their lives to studying this. I know negotiation, mediation, the process, and the theories. I’ve trained for decades in this. But I don’t pretend to be a religious scholar. I can explain empirically why certain issues are important, but in fact, the clergy or community members I’m talking to are far more likely than me to be able to give me the religious justifications for what I’m espousing—from careful listening to understanding the other side and the importance of dignity and respect.

As an outsider, I always try to enter a space with humility. I also think it’s equally valuable for clergy, whether they are serving as mediators or negotiators, to be humble (and many of them are). I feel and demonstrate that I am open to advice on how to deal with the problem. [But] once I had an experience with a member of the clergy who had no interest in talking to parents of a Bar Mitzvah boy about their expectations [for the ceremony]. It was a straight line—God, Halakha, rabbi—you (parents) follow. I found this attitude deeply unsatisfying, to say the least. Humility on all sides is one of those things that helps resolve disputes. The other thing is curiosity: “Let me understand why this is important to you; let me understand where you are coming from; tell me more about that.” For me, the best conversations in the Torah occur when people are curious—when they want to know more. Both humility and curiosity are values that are consistent with our religious tradition and are effective in terms of resolving disputes.

What have you learned from your experience in providing mediation for religious communities or training their members to negotiate? What “religious” lessons can be helpful in providing mediation for business entities or other secular organizations?

It continues to be interesting to me that there are professionals across the board—like clergy, but also architects, doctors, scientists—who are outstanding in their profession and still don’t have communication, negotiation, or mediation as part of their professional training. It’s not clergy’s fault, if they were not trained, that they would find themselves in the situation of conflict. It’s very similar to, say, an architect going to a couple and trying to discuss with them how to build the house. The couple may have a huge argument over the placement of the garage or the garden, while the architect just wants them to get along because he or she needs that to happen but has no expertise in mediating disputes. Think also about a doctor with a family bickering around the bed of the patient who is not doing well. The doctor needs to provide medical service but ends up mediating and talking to the family.

My point is that those are important skills across the board. It’s important to tell clergy, “You’re not alone. Let’s read up on communication, get training, and get that experience.” It’s important if clergy can ask a senior fellow not only about writing a good sermon but also about managing a variety of conflicts—a family conflict or a parent/teacher conflict at a Sunday Hebrew School—because, at the end of the day, the buck stops with you and you’re the one everybody wants to bring in. Passing this knowledge from senior to junior clergy matters and recognizing this is a shared experience sometimes can be very helpful for managing the congregation.

In terms of “religious” lessons, I think one crucially important issue is understanding people’s value systems. In religious communities it’s often more obvious. When you wear your kippah or your jewelry, you literally wear your value system for people to be able to see it. This understanding is important in terms of persuasion because when you are negotiating or mediating a conflict, you need to understand where somebody is coming from and what their worldview is. If you understand the value system, how they interpret and live their value system, how their language works, how to use metaphors or pitch your humor—all this makes you more persuasive. This is a helpful lesson for outside of religious communities as well. Let’s not leave those lessons only within a community where we know the value system; let’s take those lessons elsewhere and try to understand people’s value system, wherever it is coming from. This is a good lesson that we can take from religious communities and recognize that everybody has a value system. It might be less obvious, and it’s worth exploring.

Does this mean that, while learning these lessons from your professional life, you’re becoming more aware of your own religious tradition?

Absolutely. I love the fact that, totally unexpectedly, training for religious communities has become a part of what I do, especially in the last five years; I have helped individuals negotiate, and I get to hang out at rabbinic and cantorial conferences. This has made me read and think about my own religious tradition in many ways. My mother will tell you that I did not willingly go to Hebrew school at all. I cut class, talked back, and was not known for “Yay, religion!” when I was growing up. So I view this as a gift that I get to come back and be within these communities. This is a blessing to me. If I can help the clergy and Jewish communities manage conflicts better, I do think it’s God’s work. It’s helping my community, and I’m honored to be able to do this work.