Kristina Arriaga is president of the advisory firm Intrinsic and a former vice chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. This post is excerpted from an article in the December 2023 special issue of The Review of Faith & International Affairs commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The two special interests that have tried hardest to influence the Declaration are the Catholic Church and the Communist Party—the former with considerably more success than the latter!

—John P. Humphrey’s diary, 22 November 1948, Paris

The reality of the world situation is that there exist certain concentrations of power, U.S.A., U.S.S.R. . . . But in the United Nations, the representatives of Cuba and Chile . . . play a role that sometimes equals that of the great powers.

—John P. Humphrey’s diary, 24 November 1948, Paris

The story of the making of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is, essentially, the story of a group of men and women who brought to the drafting table their deeply held convictions about what makes us human, the provenance of our rights, and our individual and collective duties and obligations. Naturally, for some delegates, these convictions grew out of their faith. This essay reflects on the lesser-known but substantive contributions made to the framing of economic and social rights in the Declaration by two charismatic delegates, Hernán Santa Cruz, from Chile, and Guy Pérez Cisneros, from Cuba. It unravels the mystery of why their contributions have been largely forgotten and reflects on how their faith was shaped by the circumstances in which they lived and, in turn, shaped the economic and social rights in the Declaration. Their perspectives are gathered from their writing, secondary literature, and the candid observations of a chronicler of the drafting, John P. Humphrey, whose unfiltered diaries were published after his death.

“For This, He Should Burn in Hell.”

In his memoir and private diaries, John P. Humphrey, the first director of the United Nations Human Rights Division, paints a vivid picture of the role Guy Pérez Cisneros (Cuba) and Hernán Santa Cruz (Chile) played in the drafting and debates regarding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the Third Committee.

Of the Cuban delegate, Humphrey writes in his memoir, “Highly intelligent, Pérez Cisneros used every procedural device to reach his end. His speeches were laced with Roman Catholic social philosophy.” In his private diary, published after he died, Humphrey is less circumspect: “He has wasted more time and caused more difficulties than any other member of the committee. For this he should burn in hell.”

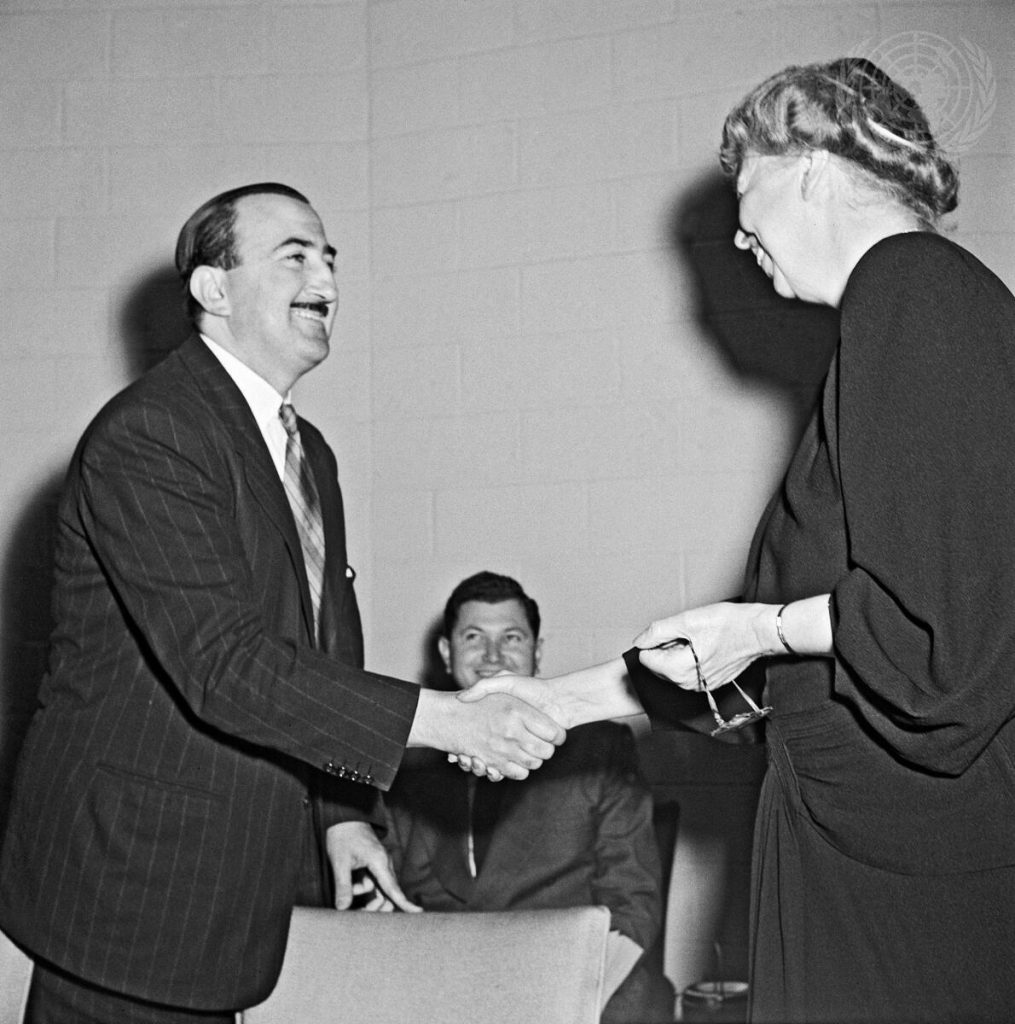

Throughout his journals, Humphrey seems kinder to another Catholic delegate with whom he had a closer relationship, Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz and Humphrey had been part of the initial drafting committee that negotiated the Declaration’s text in the Human Rights Commission before it went to the Third Committee. Humphrey had visited Santiago several times where, at Santa Cruz’s home, he had met two future presidents of Chile, Eduardo Frei Montalva (leader of the Christian Humanist movement) and Salvador Allende (a socialist), leading Humphrey to write in his memoir: “A man who could be friendly with two such different personalities was likely to be politically eclectic.”

One must wonder why Pérez Cisneros and Santa Cruz, initially cast by Humphrey as protagonists in the story of the days that would shape the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, were largely forgotten. Or why their contributions to the economic and social rights enshrined in the Declaration are widely and wrongly attributed to the representatives of the Soviet bloc.

Even now, at the 75th anniversary of the Declaration, despite the fine accounts of these delegates’ influence in the works of Mary Ann Glendon and Paolo Carozza, among others, at least one historian has emphatically stated, as recently as 2022, that Catholics “were not in the room,” cast Perez Cisneros’s contributions as minor, and identified Santa Cruz solely as a socialist, and not a Catholic, implying that being both socialist and Catholic is an impossibility.

To what can we attribute the seemingly purposeful obfuscation of their personal faiths and their contributions to the Declaration? There are at least three probable, interrelated reasons: First, Humphrey’s diary, which constitutes a vast primary source, reveals his own complex relationship with Catholicism. He oscillates between respect and dismissiveness, attitudes that he may have projected onto Santa Cruz and Pérez Cisneros—particularly the latter, whose style irritated him.

Second, although Eleanor Roosevelt accepted economic and social rights and persuaded the U.S. State Department to do so as well, this new category of rights was viewed with suspicion, and eventually, these suspicions were heightened to a fevered pitch by tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States immediately following World War II. Since the delegates from Chile and Cuba had engaged in articulating those rights, it is not impossible to imagine that the shadow cast over those rights was also cast over these delegates.

Third, Santa Cruz (1906–1999) and Pérez Cisneros (1915–1953) lived on a hyphen between democracy and dictatorship in their countries, between European and Latin American versions of Catholicism, between the elite circles in which they moved as Creoles and the conditions of the poor in the countries in which they lived. They came from countries that endured dramatic political churn in the decades following the Declaration, including periods of severe human rights violations that are unaddressed in Chile and ongoing in Cuba. As Carozza writes, these countries are often viewed as the “objects of human rights concerns” rather than “contributors to human rights thinking.”

Santa Cruz’s and Pérez Cisneros’s Indelible Contributions

Nevertheless, despite the shadows cast over these figures, a close reading of the records reveals that they left an indelible mark on the Declaration, particularly in regard to economic and social rights. One only has to examine Santa Cruz’s powerful remarks in 1948, the day before the Declaration was adopted, in which he said the Declaration was “revealed” in three articles: Article 4, right to life; Article 22, right to economic, social, and cultural rights “indispensable for [human] dignity”; and Article 29, the “need for a just social order and a peaceful international order—the two elements essential for the exercise of basic human rights.”

As a Creole, Santa Cruz knew human rights had a different meaning in Paris than in Santiago. For him, the demands of Catholic social thought could only be achieved through economic development. These sentiments can be traced to a Jesuit education, his upbringing in a familial household deeply committed to public service, and his belief that Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum had revolutionized the Catholic Church’s approach to the rights of the working man.

Likewise, French-educated Pérez Cisneros, also a Creole, was influenced by his experiences upon arriving in 1933 as a university student in a newly and briefly democratic Cuba, in the interlude that saw the drafting of the 1940 Constitution. Regrettably, this period would not last long and would be followed by the Batista coup in 1952 and the Castro coup in 1959. However, during Pérez Cisneros’s short life—he would die suddenly at 38 years old in 1953 of a brain hemorrhage—he found himself at the forefront of an intellectual, artistic, and political movement seeking a Cuban identity fueled largely by Catholic social teaching. He co-founded Orígines, a magazine featuring translated works of Saint Augustine, G.K. Chesterton, and French Catholic authors Leon Bloy and Simone Weil, along with other like-minded Cubans, most of whom were indisputably Catholic. Toward the end of his life, there is evidence he was working on creating a Cuban Christian Democrat Party.

Pérez Cisneros insistently, to the frustration of Humphrey and other delegates, reminded the drafters of the Declaration that rights were not solely “individualistic” and that there must be recognition of the duties of the state, which included, but were not limited to, recognizing the social and economic rights of individuals and their families. This is confirmed by Santa Cruz, who recalls in his memoir that Pérez Cisneros had pushed for the concept of duties because he feared “insufficient emphasis on duties and too much emphasis on the individualistic side of man’s character.” Pérez Cisneros’s legacy lives in the Declaration, most evidently in the inclusion of the phase “and his family” in Article 23 (Article 21 during the drafting), which to this day reads as he suggested.

Transformative Figures

This is an obviously abbreviated analysis of Santa Cruz’s and Pérez Cisneros’s lives on a hyphen, but it sufficiently demonstrates that they were liminal figures at the threshold of a human rights doctrine whose contributions were numerous, innovative, and substantial. Their understanding of the Catholic faith illuminated the times in which they lived and undeniably contributed to their vision of human rights—rights they viewed not solely as individual strands but as part of a larger and stronger woven fabric of humanity. A pity they have been mostly forgotten, for they deserve to be recognized for their pivotal role in drafting the Declaration.