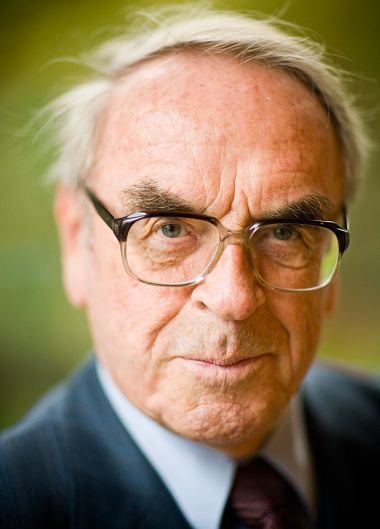

Zoran Grozdanov is an associate professor at the University Center for Protestant Theology Matthias Flacius Illyricus, University of Zagreb.

On 3 June 2024 one of the foremost theologians of the twentieth century, Jürgen Moltmann, died. He was most acclaimed in academia for his book Theology of Hope, first published in 1964 (English translation in 1967) and featured on the cover of The New York Times in 1968. Moltmann is even more famous outside the academic community for his 1971 book The Crucified God. He authored many books covering all fields of Christian theology: Christology, doctrine of God, eschatology, ecclesiology, and more. Moltmann is also widely acclaimed as the theologian about whom was written the largest number of books during his lifetime—more than 500.

Jürgen Moltmann was born in Hamburg in 1926. His grandfather was a Freemason and the Grand Master of Heinrich zum Felsen Lodge. In his youth, he was impressed with Einstein and Heisenberg and wanted to study physics. However, his plans were interrupted by World War II when he was recruited to an anti-artillery battery at the age of 17, in Hamburg. This recruitment proved to be one of the milestones for his later theology; the killing of his friend in a 1944 Allied airstrike prompted him to shout for the first time, “God, where are you?” and “Why was I not killed instead of my friend?”

Those two questions, as well as that event, haunted him for the rest of his life and gave a specific spirit to his theology. After the end of the war, he was taken by British forces to a labor camp in Scotland, where he was first introduced to Christian faith and first became aware of German atrocities and concentration camps.

After his release from the labor camp, he returned to Germany where he began studying Protestant theology at the University of Göttingen. His professors were Otto Weber and Hans-Joachim Iwand, the latter of whom was particularly influential on Moltmann and introduced him to the theology of the cross. Due to frequent electrical outages, Iwand delivered many of his lectures by candlelight and with such passion it was as though Luther himself were present. Iwand’s theology of the cross, which he believed must be placed in the center of Christian theology, as the death of God for the sake of the Godforsaken, especially after the Holocaust, became the central pillar of Moltmann’s theology.

After finishing his theological studies, Moltmann became a pastor in a small village near Bremen, after which he joined Kirchliche Hochschule in Wuppertal, operated by the Confessing Church, which had exerted strong resistance to Hitler during the Nazi period. While teaching in Wuppertal, he started to write Theology of Hope, and it immediately caught the attention of the academic community. In 1967 he became a professor of systematic theology in Tübingen, where he remained until his retirement in 1994.

Theology Directed to the Future

The shock that Moltmann’s Theology of Hope provoked is sometimes compared to the publication of the second edition of Karl Barth’s Letter to the Romans in 1922. Charged with thinking about God after the Holocaust and especially with the emergence of the “decade of freedom,” as he called the 1960s, Moltmann wrote a book that opened Christian theology toward the future. Some commentators call his Theology of Hope “baptized Ernst Bloch” since the publication of Bloch’s book The Principle of Hope, as Moltmann confessed, was the first impetus for writing his book.

He asked himself why Christian theology gave up on the future and why it gave up on its public relevance? The key issue was not only to change the emphasis of theology; rather the task was much more ambitious—how to speak about God when theologians are almost always trained to speak about him in existential terms or in terms of complete divestment from any public relevance. The theology of Moltmann’s time was marked by the existential theology of Rudolf Bultmann and, especially, by churches’ inability to speak out against Hitler’s regime.

How does Christian theology do away with talk of God as a Savior of the soul, which divests theology and the Church of power to speak against inhumane politics? In short, Moltmann took on the Jewish concept of God who walks in front of his people and guides it toward the promised future, instead of speaking of God “in us” or “above us.” This change of direction enabled Christian theology and the Church to reimagine the future in the light of eschatology. Moltmann’s famous statement from the very beginning of his Theology of Hope—“From first to last, and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology, is hope, forward looking and forward moving, and therefore revolutionizing and transforming the present”—struck a nerve of the time and opened many possibilities for an imagined future. It was no wonder that this very book was a major influence on Latin American “liberation theology” with its emphasis on reshaping the present according to God’s promised future. But what is this future like?

Theology Centered on the Cross

Moltmann answered that question, elaborating on the content and shape of the present as transformed by the future, in his groundbreaking book The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology.

In this book, which was the source of fierce debates and an inspiration in academia, in churches, and even among men and women in prisons, Moltmann did a certain salto mortale—from the trumpets of Easter to the laments of Good Friday. The whole book is dedicated to the meaning of the passion and the death of Christ on the cross, which also helped Moltmann expand the horizons of Theology of Hope. He wrote that the content of God’s promised future, according to which the present should be transformed, must be found in the meaning of the cross. He deliberately dedicated much of the book to Jesus causae crucis, that is, the reasons for Christ’s death on the cross.

Jesus, according to Moltmann, was crucified because he was blasphemous toward the Law, rebellious toward the political order, and Godforsaken in relation to his Father. Why are these emphases important for Moltmann? He wanted to make sure his readers understood that Christ’s sacrifice is not only an event of the salvation of the soul but is a public event, and that anyone who wants to follow Christ must take up the cross with utter seriousness, as the public event.

Consequently, Christian faith has the power to transform the present and to combat (yes, combat) inhumane politics an alienated Churches’ God-talk. But again, what are the standards with which to transform the present? Moltmann responds with the standards of the cross, and for Moltmann, the cross is far from the symbol of mere comfort and certainty of one’s own salvation, let alone the symbol of identity. This last usage of the cross is particularly important nowadays when the cross represents the barrier and the border of one’s own identity in contrast to other, non-Christian identities.

That is why Moltmann opens The Crucified God with a strong claim: “The cross is not and cannot be loved.” Borrowing from his friend Johann Baptist Metz, with whom he formed a “new political theology” in Germany, he claimed that Jesus didn’t die between two candles on the altar but between two criminals in Golgotha. (Moltmann was the master of the book openings—just like Jacob Taubes who said in his The Political Theology of Paul that if you get the title of the book right, you will know the content of the book. So it was with Moltmann: if you get his first sentences right, they explain the book.)

The cross, as the means for transformation of the present, points to Jesus—that is, toward all those who are persecuted and downtrodden for religious, political, and social reasons. God’s future belongs to them, and the transformation of the present must be performed with putting in the center the persecuted and the victims of the society—either political or religious. In that sense, too, Moltmann was revolutionary: “Theologians served to explain the worlds, they must now transform it,” meaning that the Christian must not rest until the Church—society—is built from the view of the victims, not the perpetrators. Not Christian society. Not Christian nation. Not Christian civilization. And not Christian values. And that is why we should read Moltmann, even more than when his books first appeared.