Ronen Shoval is dean of the Argaman Institute of Advanced Studies and head of the Herzl Program in Philosophy and Culture. This post is based on chapter 3 of his book Holiness and Society: A Socio-Political Exploration of the Mosaic Tradition (Routledge 2024).

On Capitol Hill, the seat of the U.S. Congress, 22 relief portrait plaques are installed above the gallery doors of the House Chamber. These plaques, collectively known as the Lawgivers, depict figures noted for their foundational contributions to the principles underlying the concept of law. Among these figures are Hammurabi, Justinian, and Solon, lawgivers whose ideas shaped legal thought across civilizations.

However, one figure among these lawgivers stands distinctively apart—Moses. Unlike the others, Moses is not depicted in profile but is shown in full face, gazing outward from the center of the north wall, directly opposite the Speaker’s seat. His position is symbolic; it reflects the profound and enduring impact of his teachings on concepts of justice, law, and governance.

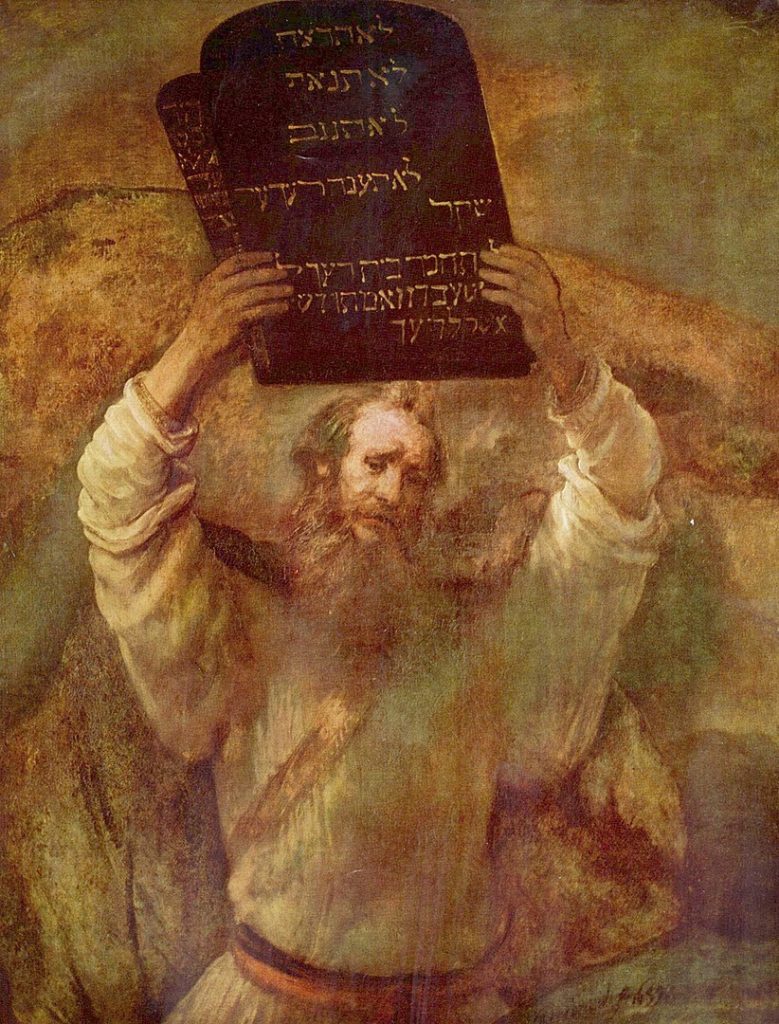

Crossing the street from the Capitol building to the U.S. Supreme Court, Moses’s presence looms large once again. In the central hall above the nine justices, Moses is depicted standing, holding the tablets of the Ten Commandments, his eyes cast down on the judges below. This image reinforces the deep connection between Moses’s ethical teachings and the foundations of modern legal thought. It is as if Moses watches over the deliberations, reminding the Court of the timeless principles that should guide the pursuit of justice.

The architects of these spaces chose wisely. Unlike the pharaohs and kings of ancient times who sought to immortalize their legacies through grand monuments and temples, Moses left behind no physical structure to enshrine his memory. Instead, his legacy endures through the power of ideas—laws, principles, and ethical teachings that continue to inspire and shape civilizations.

The Pentateuch, traditionally attributed to Moses, is not merely a religious text but a profound work of social and political thought. It tells the story of a people’s transformation from slavery to nationhood, guided by a vision of justice, holiness, and ethical governance. Moses’s vision is not concerned with abstract political theory or systematic studies of forms of government, as found in Greek philosophy. Instead, it offers a comprehensive social theory that touches on all aspects of society—law, ethics, leadership, and the relationship between ruler and ruled. Moses’s teachings provide a blueprint for constructing a just and ethical society, one that aspires to be a beacon of moral and spiritual light for all nations. This Mosaic vision of a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” challenges the conventional separation between the sacred and the secular, proposing that holiness is not confined to the private realm of personal belief but is a collective, societal aspiration.

The Sacred and the Secular: An Interwoven Tapestry

In modern Western thought, religion is often relegated to the private sphere, separated from the domains of politics, law, and public life. This separation stems from Enlightenment ideals that sought to protect individual freedoms by confining religious expression to the personal realm. However, the Mosaic tradition defies this compartmentalization. Holiness, in the Biblical sense, is not limited to religious rituals or confined to places of worship. It is an all-encompassing vision that seeks to integrate the sacred into every facet of life, from governance and legal structures to ethical norms and societal values in everyday behavior.

The Biblical injunction to be a “holy nation” (Exodus 19:6) invites a rethinking of the relationship between the sacred and the secular. Holiness appears as a public matter—as a category of the political—rather than a private matter. This concept challenges the modern liberal notion that religion and politics must remain distinct and suggests that holiness can and should inform the public sphere. In this view, holiness is not merely a personal pursuit but a communal goal that shapes the identity and mission of the nation. It offers a model for integrating ethical and spiritual values into the very fabric of society, promoting a holistic approach to justice, governance, and communal life.

This integration of the sacred into the public realm raises important questions about how societies define their ethical foundations. Contemporary democracies often rely on values like human rights, equality, and freedom, which, while influenced by secular and even anti-religious philosophies, also draw inspiration from religious sources. For example, the idea that “all men are created equal” echoes the biblical concept that every person is created in the image of God (Genesis9:5–6). The Mosaic model underscores that even when modern ideologies depart from religious beliefs, they often retain key moral insights from these ancient traditions. Holiness, in this context, is not a mystical or abstract concept but a practical framework for building a just society that upholds values of truth, justice, and righteousness.

The concept of sacred politics envisions a society striving to implement divine ideals, offering a fundamentally different approach to societal challenges. The goal of a holy society is to become an exemplary community that inspires humanity through its actions. Just as Brazil is synonymous with soccer, Japan with sushi, and the United States with capitalism, a nation guided by sacred values aspires to be synonymous with a distinct morality—one based on unique assumptions. In economics, for example, the Bible does not advocate capitalist or socialist systems but instead introduces the Jubilee.[1] The model, rooted in collective holiness, provides an alternative way to tackle social challenges such as poverty, terrorism, healthcare, arms control, etc. A community guided by the values of collective holiness would navigate life’s complexities uniquely, offering a vision that urges other nations to reconsider their societal models. This aspiration highlights the potential for a society that weaves ethical and spiritual dimensions into the public sphere, setting a new standard for human flourishing.

Holiness as a Political Institution

In the Mosaic tradition, holiness transcends individual piety and becomes a collective mission that defines the very essence of the community. It functions as a political institution in its own right, influencing the laws, customs, and ethical practices of the nation. Unlike contemporary political systems that often seek to separate moral considerations from governance, the Mosaic model integrates them, suggesting that the pursuit of holiness is not a private endeavor but a public responsibility.

Collective holiness operates more deeply than the “social contract”; it is a covenant that binds the nation to a higher ethical standard. It serves as a guiding principle for governance, shaping policies and laws that reflect the community’s commitment to divine values. This approach stands in stark contrast to modern political systems that often prioritize procedural justice over substantive moral goals. In the Mosaic vision, the legitimacy of political authority is not derived from power or popular consent alone but from its alignment with divine justice and ethical imperatives.

The concept of holiness as a political institution challenges the diverse assumptions that emerged in the post–French Revolution era about the role of religion in public life. The Mosaic tradition invites us to consider how sacred principles can inform and elevate collective and individual life, guiding it toward a higher standard of justice and moral integrity.

Autonomy and the Rejection of Coercion

A fundamental aspect of the Mosaic understanding of collective holiness is that it cannot be imposed through force or coercion. If holiness is compelled, it loses its true essence. The Mosaic tradition emphasizes the absolute autonomy of the individual, including the freedom to reject divine commandments. This principle of free will is central to the ethical framework of the Torah, which opposes religious coercion and insists that commandments have no religious value unless they are performed voluntarily.

Moses’s teachings do not seek to compel obedience just through fear or force; instead, they aim to persuade, inspire, and guide individuals toward ethical living.[2] This respect for personal autonomy reflects a profound commitment to freedom of choice as the foundation of true holiness. The rejection of coercion underscores the Mosaic tradition’s broader vision—a society that shines not because it enforces conformity but because it inspires voluntary adherence to a higher moral standard.

This approach stands in contrast to many modern governance models that rely on external enforcement to maintain order. The Mosaic model, by contrast, highlights the transformative power of moral persuasion and the importance of individual choice in the pursuit of collective holiness. It challenges us to build communities that respect personal autonomy while fostering a shared commitment to ethical values that uplift and unite.

The Role of Law in Sanctification

The Mosaic legal system is not merely a set of rules to regulate behavior; it is an instrument of sanctification. The laws of the Torah are designed to cultivate a society oriented toward higher moral objectives, integrating justice, compassion, and fairness into the everyday lives of the community. The legal framework of the Mosaic tradition goes beyond punitive measures; it seeks to sanctify the community by embedding ethical values into its legal and social structures.

One of the most profound examples of this is the observance of the Sabbath, a commandment that transcends mere religious ritual to serve as a powerful sociopolitical statement. The Sabbath mandates rest for all members of society, including servants, foreigners, and even animals, reflecting a radical vision of equality and human dignity. It challenges the relentless pursuit of economic productivity and affirms the inherent value of every individual, regardless of their social or economic status.

The Sabbath (Exodus 20:10) goes beyond being a mere day of rest; it stands as a declaration of freedom and a reflection of a society’s dedication to higher principles. It embodies the Mosaic vision, where laws are not simply tools of control but expressions of the community’s deepest values. By sanctifying time and prioritizing rest and reflection over material pursuits, the Sabbath presents a counternarrative to modern values that frequently place wealth and power above all else.

Collective Sanctification and Social Ethics

The Mosaic vision of a “kingdom of priests” (Exodus 19:6) redefines the role of leadership in profound ways. Everyone is invited to become priests. In this way, the perfect society serves all of humanity. In this framework, leaders are not mere administrators but stewards of the community’s sanctity. They are entrusted with guiding the nation toward its collective mission of holiness, ensuring that laws and policies reflect the ethical imperatives embedded in the covenant. Moses was known for his humility and lack of speaking ability (Numbers 12:3; Exodus 4:10). This model of leadership challenges contemporary notions that often prioritize personal ambition, technocratic expertise, or economic success.

Instead, Mosaic leadership demands moral exemplarity, holding leaders accountable not just to their constituents but to the transcendent ideals of justice and righteousness. This alignment of leadership with the sacred underscores the profound ethical responsibilities of those who wield power, reminding them that true authority comes not from might or manipulation but from service to the higher good.

Rituals and ceremonies in the Mosaic tradition also play a crucial role in the public sanctification of the community. Far from being empty formalities, these rituals are potent expressions of collective identity and moral commitment. They serve as tangible reminders of the nation’s covenantal relationship with the divine, reinforcing the ethical standards that guide public and private life. In a world where communal rituals have often been replaced by individual expressions of spirituality, the Mosaic model offers a vision of how shared religious practices can serve as powerful unifying forces, upholding communal values and reinforcing social bonds.

A Vision for Contemporary Society

The Mosaic tradition’s approach to holiness as a political category offers profound insights for contemporary debates on law, governance, and social ethics. By envisioning a society where the sacred and the secular are not separate but interwoven, it provides a model for integrating moral principles into the fabric of public life. In doing so, it challenges us to rethink our assumptions about the role of religion in the state and society and to explore how ancient wisdom can inform modern governance. As we face the challenges of an increasingly fragmented world, the call to be a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” remains a powerful reminder of the potential for holiness to transform society and achieve the vision of a “city upon a hill.”[3] By fulfilling this vision, such a state does not serve itself but becomes a model of inspiration for all humanity. Thus, as Moses envisioned, it becomes God’s partner in history itself.

References:

[1] The Jubilee system is an economic model from the Bible that includes cycles of obligations and rights related to various legal aspects, such as the ability to work the land, enjoy its fruits, lend money, and more, every seven years. After seven complete cycles, in the 50th year, a more radical process takes place. Broadly speaking, the system can be described as highly capitalist for 49 years, with the 50th year marked by a very extreme reform that aims to restore balance to the system, releasing debts, returning properties to their original owners, and rebalancing the social and economic structure between the rich and the poor.

[2] See Deuteronomy 6:18; 30:19; 2 Yehezkel Kaufmann, The History of the Israelite Faith: From Ancient Times to the End of the Second Temple 590–91 (Hebrew; Tel Aviv, Mossad Bialik-Dvir 1964–72).

[3] From Puritan John Winthrop’s lecture or treatise, “A Model of Christian Charity,” delivered on March 21, 1630, at Holyrood Church in Southampton.