Dr. David Kenny is Associate Professor of Law and Fellow at Trinity College Dublin

Dr. David Kenny is Associate Professor of Law and Fellow at Trinity College Dublin

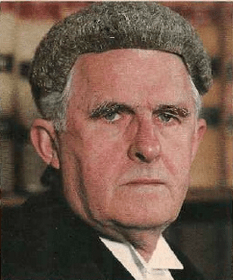

Ask any lawyer, judge, law student, or legal academic in Ireland to draw up a list of Ireland’s great judges, and one name is guaranteed to appear: Mr. Justice Brian Walsh. Sitting on the Irish Supreme Court in the heyday of its activist period in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Walsh’s fingerprints are on many of the Court’s most important and innovative constitutional judgments [1]. A pioneer of unenumerated (or implied) constitutional rights—recognizing, amongst other things, a trailblazing right to privacy—Walsh’s innovative jurisprudence was transformational in Irish constitutional law.

A friend and correspondent of famed U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan [2], Walsh—alongside colleagues like Seamus Henchy and Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh—developed Irish constitutional jurisprudence in a manner not dissimilar to the Warren Court in its heyday. His influence echoes still, even after more cautious courts in the 1990s and 2000s resiled from some of the more innovative elements of this period of constitutional expansion. Perhaps, as leading academic and current Supreme Court Judge Gerard Hogan has argued, Walsh’s constitutional vision, even if a good reading of the text, was simply too radical for judges largely wedded to the common law tradition [3].

A fascinating part of Walsh’s story is his somewhat unusual marriage of progressive constitutional jurisprudence with Catholic natural law thinking. Walsh was Catholic and was educated in Catholic schools, as almost everyone in Ireland was at the time. But he was a private person in many ways—his personal papers have not been released—so it can be hard to get a sense of his relationship to his faith and how it influenced his judging.

Walsh was not someone who was wedded dogmatically to the social and moral teachings of the Catholic Church, and this was apparent in his career prior to becoming a judge. He advised and supported Noel Browne, a pathbreaking Minister for Health, in proposing his “mother and child scheme,” which offered various forms of socialized medical care to mothers. This attracted huge controversy when proposed in the early 1950s, and the influential Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, summoned Browne to chastise him for proposing that women receive “gynecological care not in accordance with Catholic principles” [4]. The scheme was abandoned and Browne resigned. Walsh’s support of him—he followed Browne into the Fianna Fáil party after this controversy—shows that he was not always ad idem with the Catholic hierarchy on social and moral matters [5].

Natural Law and Natural Rights

Walsh’s most notable contribution to Irish constitutional jurisprudence was his natural law thinking on rights. This was at the heart of the constitutional doctrine on unenumerated or implied rights. The Irish Constitution’s core personal rights protection in Article 40.3 seemed to suggest that the Constitution protected other rights beyond those listed [6]. Walsh’s approach—to turn to the natural law to find these rights—“largely influenced” the development of the doctrine [7].

The Irish Constitution is very clear in recognizing the existence of some law above the Constitution. It talks of certain family rights being “inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law” (Art. 41). It also talks about rights of property being “antecedent to positive law” (Art. 43). Judge Walsh’s famous comments on rights and the natural law built on this text. He said these provisions of the Constitution

emphatically reject the theory that there are no rights without laws, no rights contrary to the law and no rights anterior to the law. They indicate that justice is placed above the law and acknowledge that natural rights, or human rights, are not created by law but that the Constitution confirms their existence and gives them protection.

In Ireland, he said, it “falls finally upon the judges to interpret the Constitution and in doing so to determine, where necessary, the rights which are superior or antecedent to positive law or which are imprescriptible and inalienable.” It was clear that this was not any kind of secular natural law that Judge Walsh had in mind; he noted that the Constitution acknowledged God in its preamble and elsewhere and saw God as the source of all authority [8]. He continued,

The natural law as a theological concept is the law of God promulgated by reason and is the ultimate governor of all the laws of men. … What exactly the natural law is and what precisely it imports is a question that has exercised the minds of theologians for many centuries and on which they are not yet fully agreed.

The courts would not engage, he said, in a religious debate about the nature and extent of the natural law, as this would not be appropriate in a pluralist society. So what, then, were judges to do? He suggested that they consider, case by case, whether the Constitution protected a given right and decide this based on their understanding of the constitutional values of prudence, justice, and charity, as well as the dignity and freedom of the individual, found in the Constitution’s Preamble:

[J]udges must, therefore, as best they can from their training and their experience interpret these rights in accordance with their ideas of prudence, justice and charity. It is but natural that from time to time the prevailing ideas of these virtues may be conditioned by the passage of time; no interpretation of the Constitution is intended to be final for all time. It is given in the light of prevailing ideas and concepts [9].

Essentially, Judge Walsh knew that there was a subjectivity to this approach and did not deny this. Writing extrajudicially, Judge Walsh acknowledged that a judge, in doing this, “must rely upon instinct or intuition, which, in short, means on his own moral sense or his own intelligence” [10]. Judge Walsh would not have denied that your moral sense—surely forged in part by your religious views and beliefs—has to shape your judicial judgment on such frontier questions of constitutional rights.

Theologically Framed Natural Law and Its Non-Catholic Interpretation: The McGee Case

Yet despite Judge Walsh’s highly religious and theological frame for the natural law, his natural thinking did not map directly onto Catholic teaching—far from it. He made these crucial statements on natural law rights in the 1973 case McGee v. Attorney General, perhaps Ireland’s most celebrated constitutional rights case, where the Supreme Court invalidated Ireland’s blanket ban on the importation and sale of contraception. Judge Walsh derived in this case a right to privacy for married couples that encompassed a right to decide whether to use contraception.

This, of course, was directly contrary to Catholic teachings and even to the feelings of many Irish people at the time. There was a widespread feeling that contraception was just the first step on a slope of moral decline; as one parliamentarian put it in a debate on contraception, “as soon as we have contraception in there will be abortion, divorce, euthanasia, all the other evils of venereal disease and everything that will follow ….” [11]. Judge Walsh in McGee was unmoved by the fact that many people in Ireland might still regard the use of contraception as morally wrong: “the fact that the use of contraceptives may offend against the moral code of a majority of its citizens does not per se justify an intervention by the state to prohibit their use within marriage.” Clearly, Judge Walsh’s rights reasoning may have been religious, seeped in the Catholic theology of Aquinas and others, but his finding in that case was not. Using natural law did not make constitutional rights the servants of Catholic ideology.

Walsh’s Jurisprudence Beyond McGee

Looking at other parts of Judge Walsh’s judicial legacy, we see that his liberal zeal had limits, and some of his other judgments had much in common with Catholic social mores of the time. Later in his career he sat as a judge of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, where he partly dissented in the case of Dudgeon v. UK. The Court in Dudgeon found that Northern Ireland’s prohibition on homosexual sexual acts violated the Convention. In the course of his dissenting judgment, Walsh said:

Religious beliefs in Northern Ireland are very firmly held and directly influence the views and outlook of the vast majority of persons in Northern Ireland on questions of sexual morality. In so far as male homosexuality is concerned, and in particular sodomy, this attitude to sexual morality may appear to set the people of Northern Ireland apart from many people in other communities in Europe, but whether that fact constitutes a failing is, to say the least, debatable. Such views on unnatural sexual practices do not differ materially from those which throughout history conditioned the moral ethos of the Jewish, Christian and Muslim cultures.

Judge Walsh said that privacy, while crucial in heterosexual marriage, was not necessarily crucial outside of it. Viewed this way, his liberal position in McGee can be seen as a defense of the special status of the marital bond—also valued highly in Catholic morality and social thought—in the face of Catholic disapproval of contraception.

In the earlier case of Nicolaou v. An Bord Uchtàla (the Adoption Board) from 1966, Judge Walsh had expressed very traditional views on the family in finding that unmarried mothers had significant natural rights over their children, whereas unmarried fathers, such as the applicant in this case, had almost none. He said,

When it is considered that a [child of unmarried parents] may be begotten by an act of rape, by a callous seduction or by an act of casual commerce by a man with a woman, as well as by the association of a man with a woman in making a common home without marriage in circumstances approximating to those of married life, and that, except in the latter instance, it is rare for a natural father to take any interest in his offspring, it is not difficult to appreciate the difference in moral capacity and social function between the natural father [and the natural mother] [12].

This illustrates Judge Walsh’s view of the importance of marriage and his traditional views on the roles and importance of mothers versus fathers.

In the end, Walsh’s pioneering natural law approach fell out of favor with the Irish courts. It, and a secular equivalent focusing on human personality, undergirded the large volume of unenumerated rights jurisprudence. In the 1990s, however, this doctrine, and these constitutional approaches, faded away as a more (judicially) conservative judiciary withdrew from the more activist tendencies of earlier decades. They did not believe, as Judge Walsh did, that there were appropriate guiding principles for exercising this sort of judicial judgment. As the current Chief Justice put it, writing extrajudicially, recognizing new rights “slowly ran out of steam and was permitted to come to a natural halt” [13]. Recent trends have seen a “dignity” and “personhood” approach to rights resume and a willingness by the judiciary to embrace certain new “derived” rights, suggesting a possible return to Judge Walsh’s judicial creativity, if not to the natural law [14].

Conclusion

Walsh’s relationship to his Catholicism is hard to understand. Like many liberal Irish Catholics (and many believers of all kinds), he may have had his own idiosyncratic mix of religious, moral, and social beliefs that defy easy categorization. His invocation of the natural law helped render the Irish Constitution and Irish society more liberal, but he still saw aspects of society as properly governed by a morality that was certainly not separate from religion. This duality will make him a fascinating subject of study for those interested in religion and judging.

[1] See, for example, Attorney General v. O’Brien [1965] IR 142; Meskall v. CIE [1973] IR 121; People (Attorney General) v. O’Callaghan[1966] IR 501; and of course the McGee case, discussed below. This is a very incomplete list.

[2] See Ruadhán Mac Cormaic, The Supreme Court (Penguin Ireland, 2016) 83.

[3] Mr. Justice Gerard Hogan, The Farthest: December 1972, Brian Walsh Memorial Lecture, Irish Society for European Law, 16 November 2017.

[4] Mark O’Brien, “How The Irish Times Exposed the Mother and Child Scandal 70 Years Ago Today,” The Irish Times, 21 April 2021.

[5] See Charles Lysaght, “Walsh, Brian Cathal Patrick,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, May 2012.

[6] Article 40.3.2 of the Constitution of Ireland 1937 reads: “The State shall, in particular, by its laws protect as best it may from unjust attack and, in the case of injustice done, vindicate the life, person, good name, and property rights of every citizen.” The phrase “in particular” is crucial to this reading. See Ryan v. Attorney General [1965] IR 294.

[7] Gerard Hogan, Gerry Whyte, David Kenny and Rachael Walsh, Kelly: The Irish Constitution (Bloomsbury Professional, 2018) [1.1.77].

[8] The Preamble and Article 6 of the Constitution make this clear. See my earlier blog post on this point here.

[9] All the foregoing quotations from Judge Walsh are taken from his judgment in McGee v. Attorney General [1974] IR 284.

[10] Brian Walsh, “The Constitution and Constitutional Rights” in Frank Litton (ed.), The Constitution of Ireland 1937–1987 (IPA, 1988) 106.

[11] Deputy Michael Kitt, Dail debates vol. 274, col. 918–921, 11 July 1974.

[12] Nicolaou v. An Bord Uchtála [1965] IR 567.

[13] Donal O’Donnell, “The Sleep of Reason” (2017) 40(2) DULJ 191, 200.

[14] See e.g., David Kenny, “Recent Developments in the Right of the Person in Article 40.3: Fleming v. Ireland and the Spectre of Unenumerated Rights” (2013) 36 DULJ 322; Simpson v. Governor of Mountjoy Prison [2019] IESC 81; Friends of the Irish Environment v. Government of Ireland [2020] IESC 49.