Alar Kilp is a lecturer in comparative politics at the University of Tartu.

When Churches in Central and Eastern European countries take conservative positions (either alone or jointly in the form of all-Church councils) on “culture wars”[1] values relative to family and reproductive issues as well as sexual and gender identity, the overlap with “traditional values” promoted and weaponized by the Kremlin—which includes both Russia’s political leadership and the Patriarchate of Moscow—is often obvious.

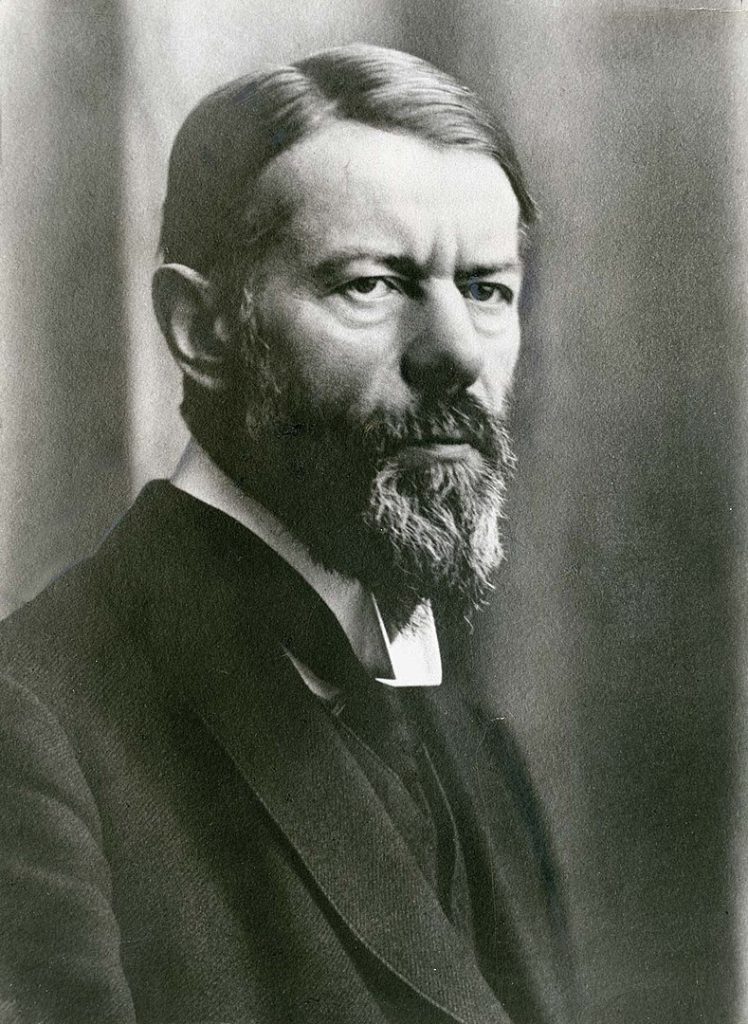

In Russia, the promotion of traditional values has an “elective affinity” relationship, where conservative positions promoted by a religious actor (the Russian Orthodox Church) and the geopolitical agenda of the Russian Federation can intuitively and coherently be associated with each other in the way Max Weber used the term elective affinity (Wahlverwandtschaft) for the perceived associations between economic behavior and religious doctrine.

However, does this mean that conservative (both religious and secular) actors in Central and Eastern Europe contribute to the Kremlin’s geopolitical agenda or promote the Kremlin’s values?

Scholars fairly unanimously agree that Russia has expressed the intention to promote “traditional values,”[2] has acted on that intention,[3] and has found many significant allies globally, based on shared moral positions.[4] Thus, it seems that Russia’s influence has contributed significantly to an emerging global conservative alliance among actors from both democratic and authoritarian contexts. This global alliance can be seen as a challenge for both peace and democracy.

However, one can also find comparative studies of religion’s role in the culture wars of Central and Eastern Europe that do not refer to the Kremlin, the Russian Federation, or the Russian Orthodox Church at all.[5] For example, an empirical study of public controversies in Bulgaria over ratification of the Istanbul Convention (the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence), equal marriage rights in Romania, and Gender Studies MA programs in Hungary does not include the study of Russian secular and religious actors as external forces involved in these “locally adapted forms of global anti-gender campaigns.”[6] Thus, in such specific studies, religious and secular forces and left- and right-wing conservatism in democratic “culture wars” have not been linked to Russia. Other studies conduct their central research without reference to Russia but note in their “discussion of findings” that “the current role of the Russian Federation” should be further explored.[7] Thus, it is possible that in some cases religious forces and actors in Eastern European “culture wars” have no direct relationship to Kremlin.

In autumn 2023, when I wrote a report on freedom of religion in Estonia (2022–23), I identified two main developments: (1) the Estonian Council of Churches opposed the extension of the right to marry to LGBTQ+ persons (although legislation establishing marriage equality was adopted by the Estonian Parliament on 19 June 2023, and the law entered into force 1 January 2024); and (2) after 24 February 2022, representatives of the Estonian government expected all Churches, but in particular Metropolitan Eugene, the head of the Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, to take a clear public stance condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

All Estonian Churches agreed on and took a negative stance on marriage equality. When in October 2014 the Estonian Parliament adopted the Registered Partnership Act, which granted the extension of family rights to same-sex partnerships, the Estonian Council of Churches (ECC) was the main civil society actor associated with attempts to block the law’s adoption.

Ten member Churches of the ECC—including the Estonian Evangelical-Lutheran Church, the Orthodox Church of Estonia (under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate), and the Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (EOC-MP)—on several occasions presented public statements condemning homosexuality as a sin not to be promoted by state laws/legal recognition and same-sex partnerships as a harmful redefinition of family and marriage.

On 6 February 2024, the Estonian Police and Border Guard Board did not renew Metropolitan Eugene’s residence permit because his public actions and statements justifying Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine were considered a threat to Estonia’s national security. While the problematic nature of Eugene’s position on Russia had been raised several times since 24 February 2022, Eugene’s responses were ambiguous but sufficient to satisfy the Estonian government until 2024.

Leaders and ministers from other Churches have voiced concerns that the Estonian government’s expectations of Metropolitan Eugene may have been excessive or inappropriate because of the state’s obligation to uphold principles of state neutrality and non-interference in the internal affairs of religious associations.[8] Nevertheless, the government decision focused solely on security concerns relative to the EOC-MP, and the two themes—Church positions on values and Church positions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine—despite running in parallel, remained independent from each other. The Estonian government and Parliament did not address the establishment of marriage equality as a security issue. And despite the common stance of all ECC Churches on traditional ideals of family and marriage, only the EOC-MP was singled out as a security concern.

Against this background, is there evidence of elective affinity between the positions of the ECC and the promotion of “traditional values” by the Kremlin? Between 2008 and 2024, the ECC has published approximately a dozen public statements on sexuality and the traditional family. One of these also includes an argument connecting traditional values with geopolitics. In an address to the Estonian Parliament on 30 April 2014, the ECC argued that the adoption of the Registered Partnership Act may also become a serious security threat because it encourages those who do not agree with the abandonment of traditional European values to seek support from the culture and the state, which uphold traditional marriage and family values as sacrosanct.

Thereafter the ECC has not repeated, elaborated, or acted on this argument. Thus, there is insufficient empirical evidence to support a claim of Weberian elective affinity between Estonian Churches’ traditionalist value positions on family and marriage and the Kremlin’s moral stances. (By implication, there is also insufficient evidence of elective affinity between the Churches’ traditionalist positions and the Russian invasion of Ukraine because the Kremlin is primarily blamed for the latter).

Even so, any bit of evidence can still be used to support a claim that the ECC narrative tends to match that of Kremlin. For example, when in 2014 an Estonian civil society actor did not support adoption of the Registered Partnership Act, the actor was characterized as “support[ing] the Kremlin’s stance.” Thus, a conservative stance was automatically identified as a stance supportive of the Kremlin. This assessment was based not on any evidence of the parties’ behavioral collaboration but on the mere overlap of value stances. Importantly, a de facto majority of Estonian society until 2021 and a majority in the Estonian Parliament until 2023 did not support same-sex marriage. It should be obvious that these majorities were not pro-Kremlin merely because of their moral stance.

Alternatively, instead of being framed as “pro-Kremlin,” the conservative stance of Churches in Central and Eastern Europe can be viewed within the framework of political cleavages in general, and through the dimensions of church/state, religious/secular, conservative/liberal cleavages in particular, that have structured European democratic politics for decades, if not centuries.[9] Or they can be assessed as political engagement of “public religion,”[10] an activity normal and legitimate in the context of democratic “twin tolerations,” where religious institutions “must be able to advance their values publicly in civil society and to sponsor organizations and movements in political society.”[11]

This is how conservatism in European democracies has functioned “as usual.” It is the Kremlin that attempts to weaponize conservative values—to use them instrumentally to advance its war of aggression and to monopolize its representation. The elective affinity between the Kremlin’s geopolitical agenda and conservatism in democratic European countries either exists or it does not. The answer depends on empirical evidence.

References:

[1] James Davison Hunter, Culture Wars (Culture Books 1991).

[2] Emil Edenborg, Anti-gender Politics as Discourse Coalitions: Russia’s Domestic and International Promotion of “Traditional Values,” 70(2) Problems of Post-communism 175, 175–84 (2023)

[3] Heleen Zorgdrager, Ukrainian Churches in Defence of “Traditional Values”: Two Case Studies and Some Methodological Considerations, 48(2–3) Religion, St. & Soc’y 90–106 (2020).

[4] Gionathan Lo Mascolo & Kristina Stoeckl, The European Christian Right: An Overview, in The Christian Right in Europe: Movements, Networks, and Denominations 11, 11–42 (Gionathan Lo Mascolo ed., Transcript 2023); Ov Cristian Norocel & David Paternotte, The Dis/Articulation of Anti-gender Politics in Eastern Europe: Introduction, 70(2) Problems of Post-communism 123, 123–29 (2023).

[5] Phillip M. Ayoub, With Arms Wide Shut: Threat Perception, Norm Reception, and Mobilized Resistance to LGBT Rights, 13(3) J. Hum. Rts., 337, 337–62 (2014); Martijn Mos, The Anticipatory Politics of Homophobia: Explaining Constitutional Bans on Same-Sex Marriage in Post-communist Europe, 36(3) E. Eur. Pol. 395, 395–416 (2020).

[6] Norocel & Paternotte, supra n. 4, at 124.

[7] Norocel & Paternotte, supra n. 4, at 125.

[8] Meego Remmel, Toward Integrity and Integration of the Church(es) Relating to the State in the Secularized Cultural Context of Estonian Society, 14(3) Religions 398, 405 (2023).

[9] Seymour M. Lipset & Stein Rokkan, Cleavage Structures, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: An Introduction, in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-national Perspectives 1, 1–64 (Seymour M. Lipset & Stein Rokkan eds., Free Press 1967).

[10] José Casanova, Public Religions in the Modern World (Univ. of Chicago Press 1994).

[11] Alfred Stepan, Religion, Democracy, and the “Twin Tolerations,” 11(4) J. Democracy 37, 39 (2000) (emphasis added).