George Walters-Sleyon is McDonald Distinguished Fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University

George Walters-Sleyon is McDonald Distinguished Fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University

About James Cone

Black Lynching in the U.S. is Black Crucifixion

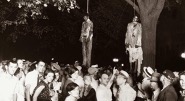

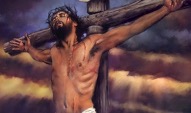

In The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Cone provides a socio-theological and intersectional analysis of the lynching tree and the cross. For Cone, “God transformed lynched black bodies into the recrucified body of Christ” (158).

Though separated by 2000 years, Cone contends that the cross signifies the “universal symbol of Christian faith,” while the lynching tree embodies the “quintessential symbol of black oppression in America.” With death as the nexus, Cones argues that the cross “represents a message of hope and salvation,” in contrast, the lynching tree “signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy” (xiii).

Though separated by 2000 years, Cone contends that the cross signifies the “universal symbol of Christian faith,” while the lynching tree embodies the “quintessential symbol of black oppression in America.” With death as the nexus, Cones argues that the cross “represents a message of hope and salvation,” in contrast, the lynching tree “signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy” (xiii). He explains: “Until we can see the cross and the lynching tree together, until we can identify Christ with a ‘recrucified’ black body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy” (xv). He argues that white supremacists’ ideology and actions depict the inherent problem of American society and White Christianity. However, while White Christians provided a religious validation, white supremacy’s philosophical and political justifications originated with the founding fathers, the courts, and the American Congress―Thomas Jefferson, Roger B. Taney, Thomas R. R. Cobb, John C. Calhoun, and Thomas Ruffin. For Cone, white supremacy generates “terror” for Black people. He notes: “Black people know something about terror because we have been dealing with legal and extralegal white terror for several centuries. Nothing was more terrifying than the lynching tree” (xix).

He explains: “Until we can see the cross and the lynching tree together, until we can identify Christ with a ‘recrucified’ black body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy” (xv). He argues that white supremacists’ ideology and actions depict the inherent problem of American society and White Christianity. However, while White Christians provided a religious validation, white supremacy’s philosophical and political justifications originated with the founding fathers, the courts, and the American Congress―Thomas Jefferson, Roger B. Taney, Thomas R. R. Cobb, John C. Calhoun, and Thomas Ruffin. For Cone, white supremacy generates “terror” for Black people. He notes: “Black people know something about terror because we have been dealing with legal and extralegal white terror for several centuries. Nothing was more terrifying than the lynching tree” (xix).George Floyd, Dreasjon Reed, Michael Ramos, Breonna Taylor, Shantel Davis, Eric Garner, Chinedu Okobi, Deborah Danner, and the list goes on.

According to Cone, “The lynching of black America is taking place in the criminal justice …That is why the term ‘legal lynching‘ is still relevant today. One can lynch a person without a rope or a tree” (163). The history of law enforcement and police brutality against Black bodies is over 400 years old. Cone explains: “The violence and oppression of white supremacy took different forms and employed different means to achieve the same end: the subjugation of black people” after emancipation (2). One of those forms was lynching. Besides, “White Americans do not dare to know that blacks are beaten at will by policemen as a means of protecting the latter’s ego superiority as well as that of the larger white middle class” (25). With the courts asserting white supremacist ideologies and law enforcement racially designed to reenslave free Blacks, “Lynching was the white community’s way of forcibly reminding blacks of their inferiority and powerlessness” (7). Unfortunately, white supremacy claims were succinctly established in the briefings of Supreme Court Justices. For example, in the Dred Scott Decision of (1857), Justice Roger Taney argued that “(blacks) had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” (7).

According to Cone, “The lynching of black America is taking place in the criminal justice …That is why the term ‘legal lynching‘ is still relevant today. One can lynch a person without a rope or a tree” (163). The history of law enforcement and police brutality against Black bodies is over 400 years old. Cone explains: “The violence and oppression of white supremacy took different forms and employed different means to achieve the same end: the subjugation of black people” after emancipation (2). One of those forms was lynching. Besides, “White Americans do not dare to know that blacks are beaten at will by policemen as a means of protecting the latter’s ego superiority as well as that of the larger white middle class” (25). With the courts asserting white supremacist ideologies and law enforcement racially designed to reenslave free Blacks, “Lynching was the white community’s way of forcibly reminding blacks of their inferiority and powerlessness” (7). Unfortunately, white supremacy claims were succinctly established in the briefings of Supreme Court Justices. For example, in the Dred Scott Decision of (1857), Justice Roger Taney argued that “(blacks) had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” (7).

The U.S. Law enforcement institution functions on the principles of Black otherization and criminalization. It is the consistent perpetuation of the “American reality” of lynching. For Cone, the frequency of lynching was “absurd” and remorseless. “Whites often lynched blacks simply to remind the black community of their powerlessness” (12). Like the horrifying and graphic murders of Eric Garner and George Floyd, lynching was a horrifying way to die and a “horrifying symbol of white supremacy” (15). According to Cone, “Whites could kill blacks, knowing that a jury of their peers would free them but would convict and execute any black who dared to challenge the white way of life” (49).

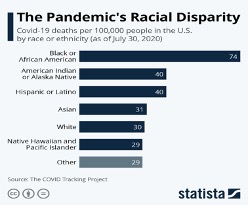

In God of the Oppressed, Cone’s goal was to describe and interpret the historical experience of living Black. The Black Experience denotes multiple experiences which include disparities against Blacks in the U.S. health system, and the use of Black bodies as guinea pigs.

The U.S. mortality rate of COVID-19 in the first half of September 2020 is over 200,000. Of this number, Blacks are dying at 2.371 times the rate of Whites with an average of 94 per 100,000. According to the A.P.M. Research Lab, “If they had died of COVID-19 at the same actual rate as White Americans, about 20,800 Black Americans would still be alive.” The disproportionate death of Blacks is mostly attributed to increased rates of concentrated forms of poverty, the health system’s disparities against Blacks, lack of easy access to necessary resources as wells as Blacks as part of the new COVID-19 essential workforce. Dr. Fauci has compared the impact of COVID-19 on the Black community to the AIDS epidemic. While Blacks’ experience of disparities in the health system is historical, his reference highlights the foundational problem of racism. “I see a similarity here because health disparities have always existed for the African American community.” He explains, “Here again with the crisis, how it’s shining a bright light on how unacceptable that is because, yet again, when you have a situation like a a coronavirus, they are suffering disproportionately.” The U.S. health system has a distrustful historyin the Black community. For Harriet Washington, “The experimental suffering of black Americans has taken many forms ” (8). The list is endless: the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the use of over 7,000 Black boys in Baltimore to find a criminal gene or Cloning Lacks’ Cells. According to Dr. Michael Byrd “Race, and its by-product racism is major factors in the U.S. health system and help define one of America’s health dilemmas” (11). For Cone, white supremacy reflects the lack of “solidarity with the oppressed.”

According to Cone, “The black church was born in slavery” (91). It came out of the “brutalizing reality of white power” (92) in protest to protect the humanity of Black people as one institution untouched by white power. “Unlike the white church, its reality stemmed from the eschatological recognition that freedom and equality are at the essence of humanity, and thus segregation and slavery are diametrically opposed to Christianity” (94). As a buffer against the angst of racism, Cone describes the Black church, its theological and liturgical identities as organic and redemptive to the Black soul. In contrast to the Black Church, Cone contends that “It was, rather white Christianity in America that was born in heresy. Its very coming to be was an attempt to reconcile the impossible — slavery and Christianity. And the existence of the black churches is a visible reminder of its apostasy” (103).

As the pioneer of white racial ideologies, Cone argues that the White Church has become an abnormality. “White conservative Christianity’s blatant endorsement of lynching as a part of its religion, and white liberal Christianity’s silence about lynching placed both of them outside of Christian identity” (132). He articulates this American dilemma as a kind of existential alienation in which the lynching tree has replaced the cross. “Every time a white mob lynched a black person, they lynched Jesus” and “The lynching tree is the cross of America” (158). Fundamental to Cone’s theological claims is the argument that God identifies with the Black experience and the Black Church because “God is black” and “Jesus is Black.” For Cone, to enslave with impunity, to lynch with impunity, and to brutalize with impunity as though Black lives do not matter and to claim the Christian identity is to exist in a state of selective cognitive dissonance and dishonesty.