Stanislav Panin holds a PhD in Philosophy from Moscow State University and is a PhD candidate in the Department of Religion at Rice University.

When viewed through the lens of modern sensibilities concerning religious tolerance, some acts of fourteenth-century Russian Orthodox Saint Stephen of Perm seem questionable.

Stephen, a missionary of the Russian Orthodox Church, was particularly renown for spreading Christianity among the polytheistic peoples of western Siberia. According to his hagiography, Stephen and his followers regularly destroyed figures of local traditional deities, which Stephen “hated with intense hatred” and intentionally sought out, in order to cut them down with an axe and set them on fire.

The locals were understandably angered by the destruction of their sacred places. Even worse was the fact that Stephen had come from Moscow. The hagiography relays the words of a pagan priest who confronted Stephen and argued that people should stick with “the gods of their forefathers.” He continued his argument by asking rhetorically, “What good could possibly come from Moscow? Is it not the source of hardships, heavy taxes, and violence?”

Saint Stephen’s example illustrates that the issue of Russian Christian proselytism was never limited to a religious dimension and was connected to tensions between the center and periphery, the colonizers and the colonized.

The Narrative of Voluntary Unification

The model in which Orthodox Christianity represents the central authorities, while traditional beliefs are tightly coupled with local identities, persists in Russia even today. In the 2019 book Buddhists, Shamans, and Soviets, Justine Buck Quijada explores the interplay of identities in present-day Buryatia, a region in eastern Siberia [1]. She discusses the importance of shamanistic beliefs and practices for local identities and the role of the Russian Orthodox Church that symbolically represents the central authorities.

In particular, Quijada describes a local celebration of City Day, a municipal holiday, in Ulan-Ude, the capital of Buryatia. The celebration opened with a ceremony, during which an Orthodox priest, who was Russian, offered bread—a traditional gesture of hospitality—to the Buryat mayor of Ulan-Ude. Quijada raises the question of why a Russian person, who was seemingly a guest in Buryatia, welcomed the local mayor, and not the other way around.

The answer is related to a particular genre of narratives about Russian history in which Russian expansion is described as a process of “voluntary unification” with new territories. According to this narrative, Russian expansion was always initiated by local elites who asked to become part of the empire and were accepted or welcomed to the larger imperial body, thus becoming part of civilized society.

Imperial Colonizing Practices

In contrast to the official vision of voluntary unification, the actual history of Russian expansion in Siberia was complex and included several attempts to integrate native Siberian peoples into Russian and, later, Soviet society.

Russian Tsar Peter I is generally considered the first to introduce a systematic policy of forceful cultural integration of native Siberians. In 1706 and 1710, he issued two decrees prescribing the burning of idols, the replacing of pagan sacred places with Orthodox churches, and the baptizing of locals. This policy was driven by the idea of social progress that Peter inherited from thinkers of the European Enlightenment. From this point of view, “a missionary became a representative not just of the Church but also of the State, which were seen as two civilizing power structures, while the process of Christianization assumed characteristics of a war” [2].

During the nineteenth century, policies in Siberia were defined by a legal framework that aimed to ensure the Russification of the colonized territories while avoiding open conflicts between Russians and non-Russians. On one hand, The Digest of the Laws of the Russian Empire (1832) recognized a special category of Siberian non-Russians and guaranteed them freedom of religion. On the other hand, the law protected the Russian Orthodox Church’s monopoly on missionary activity, allowed conversion to Russian Orthodox Christianity but not from it, and instructed the Church and police to fight against “superstitious” rituals, magic, and divinations.

The Russian Orthodox Church promptly became the major driver behind the cultural colonization of Siberia. Archbishop Veniamin (Blagonravov) (1825–92), known for his significant role in organizing missionary work in eastern Siberia and the Far East, expressed the mentality of nineteenth-century Orthodox missionaries in asserting that

[w]ith regards to people of other faiths, Orthodox Christianity should fight not only foreign faith but also foreign national identity, customs, habits, and the entire environment of the day-to-day life of non-Russians; we should convince them of the superiority of the Russian national lifestyle so that they become Russians not just in terms of their faith but also in terms of their nationality [3].

The Making of Homo Sovieticus

After the collapse of the Russian Empire, Soviet authorities introduced new policies aimed at achieving two contradictory goals: After the 1917 revolution, the Soviet government was eager to denounce the Russian Empire as an imperialist and colonialist state; nevertheless, the increasing desire to integrate former territories of the Russian Empire into a new political body led Soviet authorities to develop new colonizing practices.

A classic example of an attempt to dismantle imperial policies was the project of “nativization” (korenizatsija), introduced in the 1920s as an alternative to Russification. It involved, for example, the introduction of local names for towns and cities, education and publishing in local languages, and quotas for officials of native backgrounds.

With growing centralization under Joseph Stalin, the early policy of nativization was discontinued by the mid-1930s. However, the rhetoric of the Soviet Union as the place of peaceful coexistence of different nations remained one the most persistent traits of Soviet ideology. Thus, the 1977 Soviet Constitution included an article establishing that “the duty of every citizen of the [Soviet Union] is to respect the national dignity of other citizens, and to strengthen friendship of the nations and nationalities of the multinational Soviet state.”

At the same time, any permitted pluralism remained largely superficial. Ultimately, Soviet ideology reflected a notion of social progress not unlike the one used by Peter I to justify Russian cultural expansion in Siberia. For Soviet authorities, in maintaining a Marxist approach, the notion of progress meant that local cultures remained largely a facade whereas the true identity of any citizen was defined first and foremost by their class origin and, ultimately, by the fact that they are Soviet people.

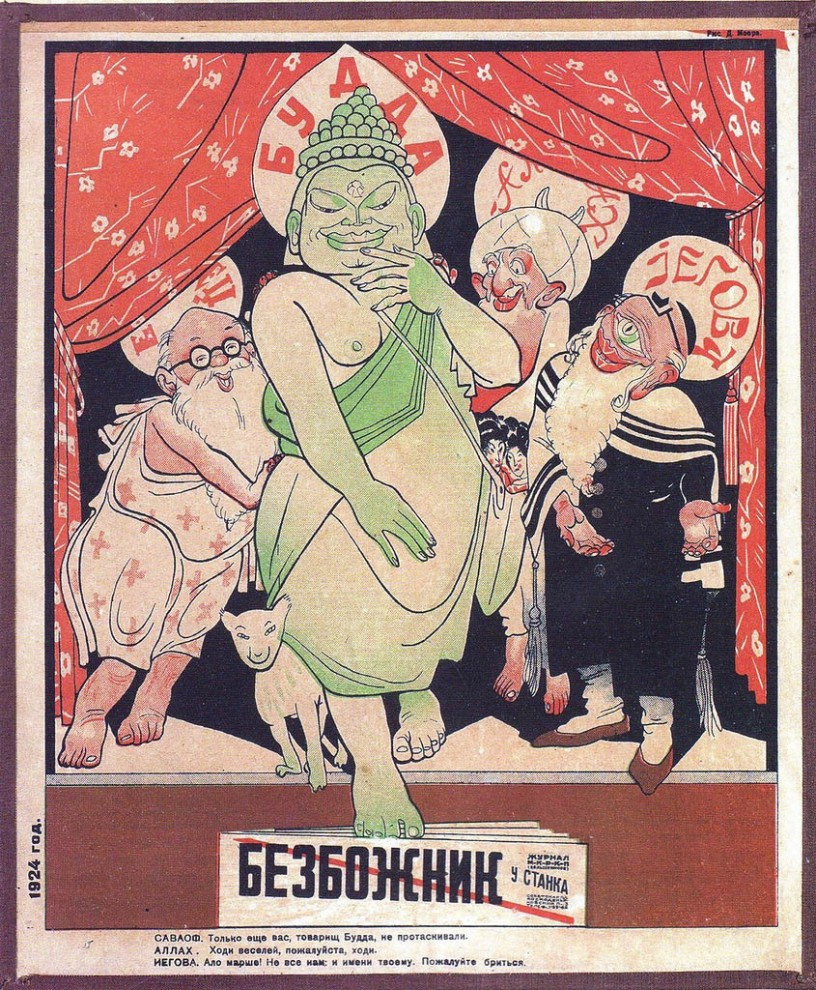

If the imperial notion of social progress implied the conversion of Siberian “savages” to Orthodox Christianity and their Russification, the Soviet notion of social progress was related to abandoning religion in favor of a new Soviet identity. Throughout the Soviet period, anti-religious campaigns, aimed at undermining the influence of Buddhist lamas and local shamans in Siberia, remained an integral part of Soviet policy.

Present-Day Russia

The Russian Constitution speaks about the “multinational people of the Russian Federation” and guarantees the equality of different ethnic and religious groups. However, the actual practices of contemporary Russia are derived from those of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union rather than from contemporary notions of human rights. Consequently, laws do not necessarily follow this constitutional principle and represent, at best, a limited vision of multiculturalism.

In particular, the 1997 Law on the Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations, while formally recognizing the equality of all religions, includes a preamble that acknowledges “the special role of Orthodox Christianity in the history of Russia” and specifically names “Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, [and] Judaism” among other, unnamed “religions constituting an integral part of the historical heritage of the peoples of Russia.” While the preamble is not legally binding, the notion of “traditional religions,” corresponding to the religions named in the preamble, became an important ideological construct separating, de facto, first-class and second-class religions in Russia.

In addition, in 2020 the Constitution was amended to mention “faith in God” as a uniting principle of Russian statehood (Article 67.2*). The reference to God in this context carries obvious Abrahamic (if not Christian) connotations and marginalizes other religions and belief systems.

For Siberian shamanism, which is not included in the list, the question of authenticity sufficient to justify its place as a part of Russia’s “historical legacy” became a central issue. In all debates concerning shamanism, its proponents tend to emphasize its role as a traditional religion of certain ethnic groups in Russia.

This becomes particularly important in the context of the ever-growing expansion of the Russian Orthodox Church that affects Siberia as well. For years, the Church has pursued a policy of expansion in the eastern regions of Russia that includes active proselytizing as well as building new churches and wayside crosses, sometimes in places considered sacred in local shamanist and polytheist beliefs.

In May 2021, a conference of Russian Orthodox missionaries issued a document specifically calling for “continuing development of the mission among native ethnic minorities of Siberia, the North, and the Far East.” Notably, this passage is situated in the document immediately after several decisions condemning the “romanticization of neopagan cults.” While it avoids explicitly mentioning contemporary shamans, the final document seemingly situates the topic of proselytism among native peoples of Siberia and the Far East within the same framework as the fight against neopaganism.

At least this is how shamans themselves often perceive the tensions with the Russian Orthodox Church. In August 2021, the leader of a shamanist organization, Kara-ool Dopchun-ool, who supports Putin’s regime, expressed his annoyance with the missionary activities of the Russian Orthodox Church and Buddhist groups. He pointed out that the cutting down of wayside crosses—a phenomenon that has been happening in Siberia for years—is a sign that the locals are tired of attempts at Russification:

There is a war against crosses in different parts of Siberia. . . . Maybe church officials think that they are doing a good deed. But angry people destroy foreign objects [that were forced] in their sacred places. . . . Put yourself in the position of the locals, who are surrounded with crosses on every side because they are suspected of being pagans. . . . As a result, good-hearted people become extremists.

Ultimately, Dopchun-ool attributed the recent growth in popularity of political opposition in Siberia to the effectively colonial policies of Russification and Christianization. Indeed, as evidenced in the recent case of Shaman Alexander Gabyshev, political opposition in Siberia and the Far East can be closely tied to local identities closely associated with shamanism.

Of course, Russian authorities, Orthodox spokespersons, and official Russian media dismiss such acts of opposition as the product of malevolent foreign instigators, mental disorders, or “destructive cults.” And yet they can be dismissed only to a certain extent. After all, it is hard not to hear behind these contemporary debates the words of a pagan priest from medieval Perm asking whether anything good could ever come from Moscow.

References:

[1] Justine Buck Quijada, Buddhists, Shamans, and Soviets: Rituals of History in Post-Soviet Buryatia (Oxford Univ. Press 2019).

[2] Sofya Melnikova, The ‘Siberian Indigenous People Issue’ in the Writings of Orthodox Missionaries in the 19th to Early 20th Centuries: The Problem of Cultural Dialogue [title translated from the Russian], 3(69) Philology & Culture 114 (2022).

[3] Id. at 116.