Nadieszda Kizenko is a professor of history at University at Albany–SUNY.

At first glance, a Russian-language prayerbook titled Mothers, Wives, Sisters, Let Us Pray for Our Warriors seems to be nothing special. It’s small. It’s made of paper. It’s cheap. Much of what’s inside has appeared in other places and other prayerbooks. And yet it represents a useful framework for looking at how the Russian Orthodox Church is attempting to engage women of faith in the current war against Ukraine. Reading this book prompts the question: what does it mean to have a book scripted by Church authorities for private prayer on a political issue?

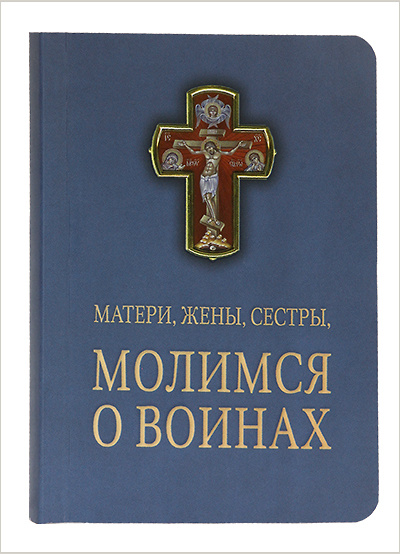

The book’s official status and its intended reach are clear. Prepared by the official Department of Service Books (otdel bogosluzhebnykh knig) of the Moscow Patriarchate, it was published in 2023 in an edition of 20,000. It consists of 160 small pages, printed in large font, so it can be easily held or carried in a pocket and read comfortably. Because of the cross on its cover and because it is sold in church shops, people might also treat this book as something to be displayed on the shelf or kept on a bedside bureau. Like icons, its presence helps to create an environment in which domestic acts of prayer are anchored to the Church as an institution. The prayers in this book and the look of this book provide ways of forging connections between communal practice in church and individual devotion.

This private-liturgical link comes through in other ways as well. Orthodox Christian liturgy often stresses the need to pray “in an Orthodox way.” The words with which an Orthodox Christian addresses God are intentionally not her own: by using the texts provided by the prayerbook, the believer tacitly acknowledges a common standard of correctness and belonging to a shared Church body. This emphasis on praying “the way one should” is why most of the prayerbook’s texts are standard liturgical hymns to saints, feasts, or icons (pp. 33–116) and so many others are familiar psalms (pp. 117–54). While the scholar might be tempted to discard such standard elements (for example, Psalm 90, or the troparion “Save, O Lord, they people, granting them victory over their enemies”) and to look only for new ones, that would miss the point: the “classic” elements are there precisely to “frame” and lend legitimacy to the new prayers, much like Aleksandr Tvardovsky successfully “framed” Solzhenitsyn’s groundbreaking novel about a prisoner in the Gulag, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, in the November 1962 issue of Novyi Mir (a prestigious Soviet literature magazine with a dissident reputation at the time), alongside texts that made it seem typical and acceptable.

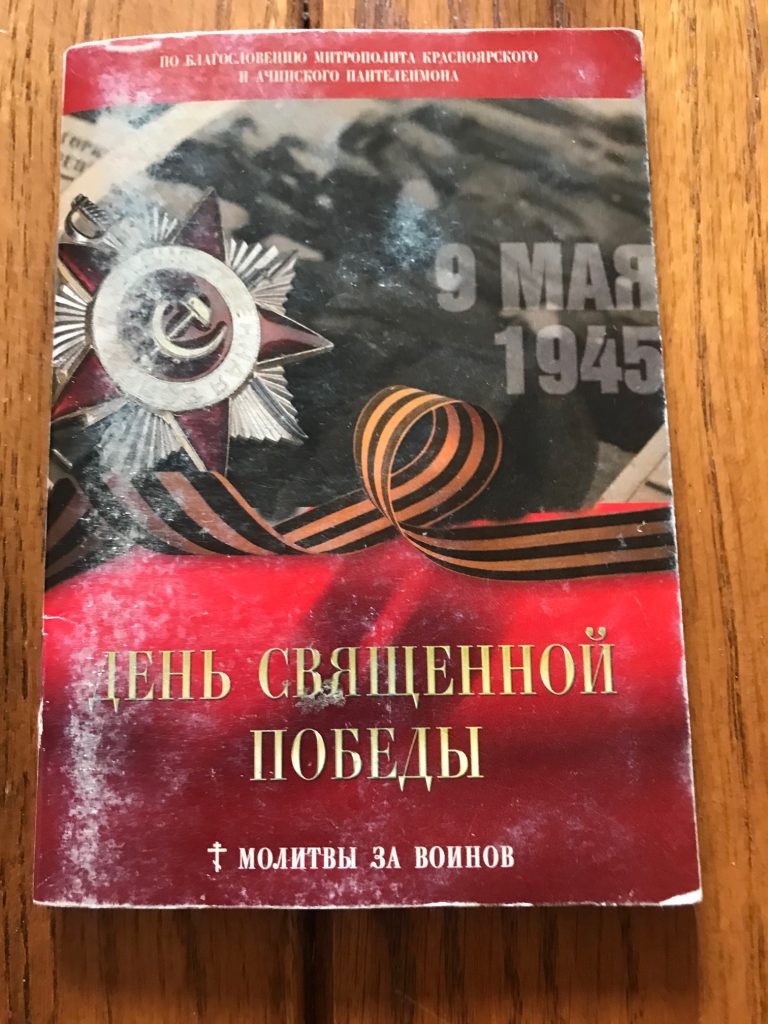

One earlier attempt at such a prayerbook was more of a hybrid production, published in Krasnoiarsk in 2020 to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Day of Sacred Victory: Prayers for Warriors began with a text by Patriarch Kirill, who emphasized that, in 1945, the USSR triumphed over “an inhuman worldview, a machine of immoral lawlessness.” Another text by Panteleimon, Metropolitan of Krasnoiarsk, went further: “Heaven won through the power of Soviet warriors” (not the reverse). The Russian Orthodox Church is praised for providing weapons for the war, and Stalin’s restoration of the Patriarchate is described as the “culmination of Church-State rapprochement in the fight against fascism.” Thus, World War II is sacralized, Stalin is redeemed, and the principle of the ROC and the state working together is affirmed. Prayers for those fighting follow almost as an afterthought. While that little pamphlet (27 pages long, in a print run of 2000) is less ambitious than the 2023 prayerbook aimed at women, it shows that the urge to tap into the symbolism of “sacred war” was present before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and at the local level, not only dictated by the center.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 prompted more attempts to link at-home devotion to Church commemoration. Nizhny Novgorod produced a wall calendar labeled Prayers for Warriors and the Fatherland, with a relevant icon and prayer for every month and the holy prince Alexander Nevsky on the cover. The women’s prayerbook is more subtle. The exhortation “Let Us Pray for [Our] Warriors” implies that the prayerbook’s compilers are one with the women whose men are at war: the verb is molimsia (let us pray), as in liturgy, not molites’ (pray ye), as in a command. By praying, women are linked both to their men and to the entire praying community. Using the word warrior rather than the modern word soldier seeks to inscribe men into an ancient and lofty tradition. Subcategories of prayers include those for when individuals are threatened by hunger, taken prisoner, or sick and wounded: “Protect him from the flying bullet, arrow, sword, fire, mortal wounds, drowning, and sudden death. . . . [L]et him escape capture and imprisonment by the enemy and the betrayal of those close to him.” The last phrase, hinting at Russian military hazing known as dedovshchina, is suggested in other prayers as well.

Buried inside familiar hymns and psalms is the “Prayer for Holy Rus,” which was also mandated for liturgical use since September 2022. Referring to Ukrainians and Russians as one people, the prayer calls on God to give “His people” victory. Given that the two are at war with one another, this might seem surprising, until one reads that unnamed “instigators” are at fault for seeking to divide and destroy the “one people of Holy Rus.” Substituting the word peace for victory in this prayer, or not reading the prayer at all, got several priests suspended. This prayer was mandated for all liturgies on the same day Patriarch Kirill preached that if someone died in the performance of his military duty, “He certainly commits an act tantamount to sacrifice. . . . We believe that this sacrifice washes away all the sins a person has committed.”

This seemed to be something new. Unlike the “atoning purification” aspect of the Crusades, Orthodox tradition does not typically claim that death in war washes away a combatant’s sins. Christ offered himself as a sacrifice—he did not kill others. Sins are washed away only by repentance, not by death “for a righteous cause.” But this view of death on the battlefield as atonement has a precedent in Russia. When blessing Ivan III’s troops before the Ugra battle in 1480, Gerontii, Metropolitan of Moscow, described shedding one’s blood in battle as “a second baptism cleansing one’s sins and earning one a place with the martyrs.” The 2020 Krasnoiarsk prayerbook also described soldiers killed on the battlefield as “martyrs reddened by their blood.”

Printed prayerbooks are not the only forum used to channel women’s piety. On 3 October 2022, Russia’s most popular social media platform, VKontakte, launched the app “Let Us Pray Together for [the/Our] Warriors” (Molimsia vmeste o voinakh). The app quickly gathered 26,000 participants, who post names and photos of their men and solicit prayers on their behalf. Twice a week the “parishioners” of this group meet for online molieben (services for the living) and pannikhidas (services for the dead). As he performs these rites, Father Evgenii Maniashkin from Smolensk reads aloud the names people have submitted. Such online “grassroots” prayer chatgroups have had a wider reception than printed prayerbooks, as evidenced in terms of both numbers and public reactions: the first such online molieben had 62,000 views—a reach far beyond the printed prayerbook’s print run—and shows women referring to Ukrainians as “fiends, non-people” (neliudi) or “fascists.”

Russian Orthodoxy is not unique in seeking the prayers of its faithful for war through novel means. Ukrainian Orthodoxy has introduced its own changes. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, for example, is moving increasingly to the vernacular Ukrainian and to digital prayerbooks as well as print ones. In addition, UOC priest Iurii Petroliuk has written a new prayerbook (molytovnyk zakhysnykiv Ukrayiny) for the defenders of Ukraine. One of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine priests has changed the traditional litany for warriors on Demetrius Saturdays to underscore that not only do “warriors” die at war but “doctors, volunteers, journalists, and peaceful inhabitants [have also] perished from shooting, bombing, and torture, without water, food, and medicine—children, women, and men.”

Such details suggest why the task of galvanizing the population to pray may be easier for Ukraine than for the country that attacked it. Ukraine is fighting for its survival, in self-defense, and on its own territory. None of that can be said about Russia. Russia needs special prayerbooks and calendars because it started the war and because it needs to convince its female population to part with their men—a task that is proving increasingly difficult. Ukraine, with much of its population mobilized and a significant portion having fled as refugees, needs no war-oriented prayerbooks aimed at women—or anyone else. They are praying and fighting already.