Dana Lloyd is an assistant professor in the Department of Global Interdisciplinary Studies, Villanova University.

The post is the part of the Religious Freedom and Indigenous Rights series

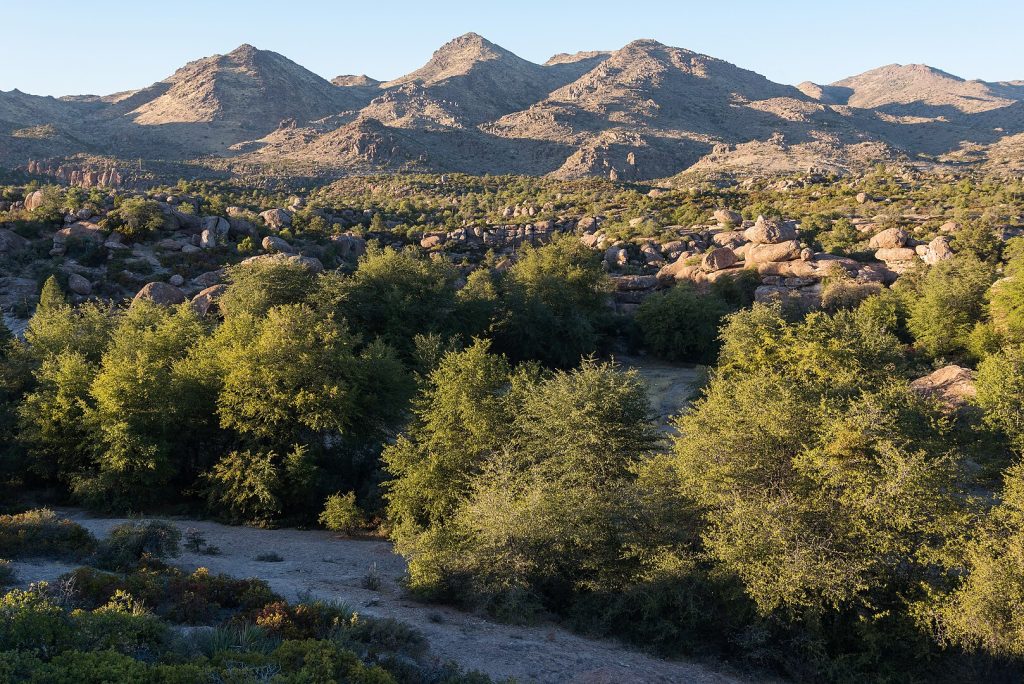

Chí’chil Biłdagoteel, known in English as Oak Flat, is the place where Ga’an (guardians or messengers between Apache peoples and the Creator, Usen) reside. It is a 6.7-square-mile stretch of land within what is currently managed by the U.S. federal government as Tonto National Forest, east of Phoenix, Arizona. Since 2014, a proposed copper mine has threatened to permanently alter the area through an underground mining technique that would cause the earth to sink, up to 1115 feet deep and almost 2 miles across. Apache Stronghold, a grassroots organization, has challenged the proposed mining plan in court, arguing that destroying their sacred sites would infringe on their free exercise of religion, a right promised to them by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993).[1]

This case is controlled by precedent from 1988 (Lyng v. NICPA), in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared constitutional a plan to build a road and log trees in the High Country in northern California, an area sacred to the Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa peoples, which has been managed by the federal government as the Six Rivers National Forest. Forty years after the Lyng case was tried in court, the Apache peoples are arguing that their case is different from Lyng, even though the cases sound very similar, and that even though the Court failed to protect the High Country from development, it should protect Oak Flat.

The main difference between the cases is that the Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa relied on the religion clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and on the American Indian Religious Freedom Act—a law described in Lyng as having “no teeth”[2]—whereas the Apache raised a claim under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which is supposed to bypass the Lyng precedent. More substantially, Apache Stronghold argues that because Oak Flat would be utterly destroyed by the mining, no religious exercise at this place would be possible at all. In the case of the High Country, the Supreme Court said that building a logging road through the sacred area would not prohibit any religious exercise, that the place would still be accessible—indeed, even more accessible—to Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa people for religious purposes. The Oak Flat case is different because the place as the Apache know it would not exist anymore if it were mined.

In its original decision, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Apache Stronghold’s claim, justifying its decision by saying that the Apache only recently revived their ceremonial use of Oak Flat and, therefore, destroying this place does not place a substantial burden on the free exercise of their religion. Religious studies scholar Michael McNally argues this justification is factually wrong. But even if it is factually correct, reading this case through the theoretical lens of settler colonialism would help us see that, if Apache ceremonial life in the area had been suppressed until recently, we should look to the settler state as culprit, as Tisa Wenger suggests. Indeed, we should question how Chí’chil Biłdagoteel has become part of the Tonto Forest rather than an Apache reservation. Another aspect of settler law is that it allows only for two stories about land to be heard: land is either property, or it is sacred. As such, all we can do is use it, act upon it, fight over it. Neither story corresponds with Indigenous cosmologies, according to which the land is not an object of rights at all.

Listen to the story Apache elders tell in court: Oak flat is a ceremonial ground, and the activities that take place there cannot be relocated. Ga’an come to these ceremonies to guide Apache people and help them heal. Coming-of-age ceremonies that take place there connect the girls and boys who undergo them to the land itself, and the land provides sacred medicinal plants, animals, and minerals. “Because the land embodies the spirit of the Creator,” if the land is desecrated, then the “‘spirit is no longer there. And so without that spirit of Chí’chil Biłdagoteel, [Oak Flat] is like a dead carcass.’”[3] The story Apache Stronghold tells the court is about religion because the case is about religion. But it is also a story about life and about relationships.

However, the first sentence in the Ninth Circuit’s decision refers to Oak Flat as “federally owned land within the Tonto National Forest.” And the court continues: “Oak Flat is a site of great spiritual value to the Western Apache Indians and also sits atop the world’s third-largest deposit of copper ore.” The land has spiritual value (to Apache peoples), and it has economic value (supposedly to everyone). Occupying no more than 2 to 3 pages of a 241-page court decision, the Apache story, according to which “everything has life, including air, water, plants, animals, and Nahagosan—Mother Earth herself,” and the Apache peoples’ desire to remain “intertwined with the earth, with the mother,” are not really taken into account by the court. As Anishinaabe legal scholar Lindsay Keegitah Borrows argues, “when governments [including courts] make decisions without adequate knowledge of stories, people suffer.”

Again, the land’s spiritual value and its economic value are in competition here; both are more important than the land’s status as relative, to whom we cannot assign a legally cognizable value. And since the competition is between economic value and religious value, or in other words, between the right to religion and the right to property, the control Lyng holds over the Oak Flat case is detrimental: According to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, “The project challenged here is indistinguishable from that in Lyng.”[4] Therefore, “Under Lyng, Apache Stronghold seeks, not freedom from governmental action ‘prohibiting the free exercise’ of religion, . . . but rather a ‘religious servitude’ that would uniquely confer on tribal members ‘de facto beneficial ownership of [a] rather spacious tract[] of public property.’”[5]

Apache Stronghold appealed to the Supreme Court, but the Court refused to hear their case.[6] Justice Neil Gorsuch, in a dissenting opinion, refers to this refusal as “a grave mistake.”[7] Grave mistake or not, given the history of Native American sacred sites cases, this outcome is not surprising. With Justice Gorsuch on the bench, and his recent opinions such as the one in Haaland v. Brackeen, one might think that tribal sovereignty is a more promising legal framework than religious freedom. However, Apache Stronghold’s reliance on the 1852 Santa Fe Treaty was quickly dismissed by the Ninth Circuit Court, which declared that the government’s statutory obligation to transfer Oak Flat abrogated any contrary treaty obligation.

Apache Stronghold says that “while this decision is a heavy blow, [their] struggle is far from over.” In addition, the San Carlos Apache Tribe has filed separate lawsuits, which are still pending. In the meantime, looking to the Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa nations, and what they have done in the face of the devastating Lyng decision, may be instructive for future action. Firstly, there is the environmental route. The Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa nations were able to lobby for the High Country’s inclusion in the California Wilderness Act (1984) so that the area has been protected by Congress, even if the Court refused to protect it. This does not seem to be an option in the current context. What about tribal law? After Lyng, the Yurok focused their efforts on establishing a strong tribal court. The tribal court has done a lot of good work in the past few decades, in areas such as family law and substance use. Recently, 30 years after the Lyng decision, the Yurok codified an ordinance recognizing their sacred Klamath River as a legal person. Shortly thereafter, without the help of federal courts, four dams were removed from the Klamath River, allowing the river to run free and the salmon, sacred relatives of the Yurok and neighboring tribes, to return to their home.

As I write this post, I wish for a similar next chapter in the Oak Flat story.

References:

[1] Apache Stronghold v. United States, 101 F.4th 1036 (9th Cir. 2024).

[2] Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, 485 U.S. 439, 455 (1988) (quoting Representative Morris Udall, sponsor of the bill that became the Act).

[3] Apache Stronghold v. United States, 519 F. Supp. 3d 591, 604 (D. Ariz. 2021) (quoting plaintiff’s court documents).

[4] Apache Stronghold, 101 F.4th at 1036, 1051.

[5] Id. at 1052 (quoting Lyng, 485 U.S. at 452–53).

[6] Apache Stronghold v. United States, 145 S. Ct. 1480 (2025) (denying cert); No. 24-291, 2025 Westlaw 2824572 (6 Oct. 2025) (denying rehearing).

[7] Id. at 2.