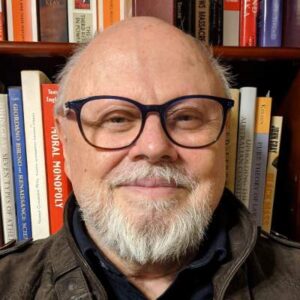

Neville Rochow QC is an Austrialian Barrister, Associate Professor (Adjunct) at the University of Adelaide Law School, and a Senior Fellow at the International Center for Law and Religion Studies.

It is a genuine pleasure to accept the invitation to contribute this introductory essay to the blog series on the constitutional space for freedom of religion. “Constitutional Space for Freedom of Religion” has been a project that culminated in the book of essays which Paul Babie, Brett Scharffs, and I edited: Freedom of Religion or Belief—Creating the Constitutional Space for Fundamental Freedoms (Edward Elgar 2020).

The project had its beginnings in an international conference held at The University of Notre Dame Australia Sydney Law School and the University of Adelaide Law School in early 2018. Expert participants from several jurisdictions added their insights to what proved to be a stimulating conversation on religious freedom and its preservation. Most of the essays in the book have been contributed by participants from the conference. As editors, we were very grateful for the two conference host institutions and the additional sponsorship that came from the J. Reuben Law School and the International Center for Law and Religion Studies at Brigham Young University. Our publisher, Edward Elgar, supported the publication process in ways that exceeded our expectations. It has been most gratifying to see the book as the fruit of combined labors of three law schools, contributors, editors, and publisher.

Readers may not be immediately familiar with the term “constitutional space.” There is emerging literature exploring its meaning, particularly with respect to freedom of religion, to which the book is a recent addition. But the notion of constitutional space is not novel. Constitutional space is a metaphor for spheres of constitutional activity. Such spaces exist under constitutional structures that provide for the spheres within which the respective arms of government operate. The legislative, executive, and judicial branches have their own defined spaces. In those spaces, they perform their functions and exercise their powers. In jurisdictions that subscribe to and respect a separation of powers doctrine, operations of each arm of government are distinct and confined to their allocated constitutional space.

However, while spaces are provided for the government, too often overlooked is the provision of separate and adequate constitutional space for the governed. Among the governed are religious practitioners who seek to engage in religious performances and pursue their conscientious beliefs with minimal state hindrance. A space must be provided within which freedom of religion can be enjoyed and where it is protected from interference. For another perspective on constitutional space, the reader is referred to Brett Scharffs’ and Brock Mason’s post on some of the specificities of the constitutional space for religious freedom and its legal cultural dimensions. Whatever may be the cultural milieu, a clear delineation of the proper spheres of religious activity is necessary. Drafters of modern human rights documents have shown a clear awareness of this need.

As appears from a study of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, human dignity is at the very center of the modern human rights enterprise. Each of these documents also recognizes as fundamental human rights, equality of treatment, and freedom of religion. However, religious freedom has two aspects. First is the unconditional right to hold a belief. Second is the right of expression, which, upon conditions of necessity “to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others,” maybe limited under International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Art.18 (3). Properly understood, dignity operates as a mediating principle between two rights that are often found in competition: the right to equality of treatment and the right to follow one’s religious conscience. Once equality and religious liberty are allocated their respective constitutional spaces, the potential for conflict between religious freedom and equality rights should be minimized.

As the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognizes, virtually all rights and freedoms are relational in their character. Even those absolute rights and freedoms, such as freedom from torture and slavery provided for in Art. 7 and Art. 8, define the way in which humans relate to one another. Every exercise of a right or freedom has a potential impact upon the rights and freedoms of others. But freedoms with which we deal on a more regular basis, such as those relating to conscience and religion, once manifested in the public sphere, are likely to intersect with other rights and freedoms. If those intersections are not to become collisions, there must be bounds to the exercise of the respective rights. It is this sense that no freedom can be unbounded; license of an unlimited kind would otherwise lead to anarchy. Since liberty can never be permitted to become license, there needs to be an examination of what rights, in relation to those of others, are comprised in any bundle of rights labeled “equality” or “liberty.” Once the content of a right or freedom is known, it should be allocated its constitutional space within which it can be exercised and enjoyed without impairment or impairing.

An example of the potential conflict between freedom of religious speech and its resolution can be found in the decision of the High Court of Australia in Clubb v. Edwards; Preston v. Avery[1], a case involving abortion clinic exclusion zones. There arose a conflict between the religiously informed conscience that sought opportunity to dissuade clinic patients from undergoing the procedure and the mental well-being of those same patients at a psychologically and emotionally-charged moment in their lives. The Court had to weigh the claim to the implied constitutional right to freedom of political communication against what exclusion zone legislation described as the “dignity” of the patient. The Court held, by a majority, that the legislation prohibiting communication within the exclusion zones was valid. The implied constitutional freedom had to yield in order to preserve the dignity of patients entering the clinics. Put another way, the bundle of rights comprising freedom of political communication, including that inspired by religious conscience, did not include a right to offend the dignity of abortion patients. The constitutional space in which freedom of expression resides does not extend to adverse effects on the dignity of others when designated by the legislature.

There are many possible ways that the avoidance of conflict between equality and religious liberty might be achieved. Those ways have been long debated and discussed. The notion of “constitutional space” adds to this discourse. Religious freedom, its content, boundaries, and relationship with other rights and liberties, and to human dignity, needs to be ascertained and made known. As a fundamental human right, religious freedom also needs its own constitutional space–one that is free from disproportionate legislative interference and the fashions of policy. The hope is to add to the conversation regarding these respective rights and freedoms. Allocating them their respective spaces is a potential way to overcome the perennial problem of conflict. The essays in Freedom of Religion or Belief—Creating the Constitutional Space for Fundamental Freedoms and the posts that will feature on this blog explore some ways in which to construct a constitutional edifice in which the space for religious freedom is well-defined and respected.

[1] See also Neville Rochow QC and Jacqueline Rochow, ‘From the Exception to the Rule: Dignity, Clubb v Edwards and Religious Freedom as a Right’ (2020) 47(1) University of Western Australia Law Review 92 http://www.law.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/3443369/5.-rom-the-Exception-to-the-Rule-Dignity,-Clubb-v-Edwards-and-Religious-Freedom-as-a-Right.pdf

Brett Scharffs and Brock Mason. Constitutional Cultures Creating Constitutional Space

Alex Deagon. Towards a Constitutional Definition of Religion: Challenges and Prospects

Jeremy Patrick. Individual Spirituality and the Future of Freedom of Religion

Brett Scharffs and Brock Mason. Three Ways of Thinking about Reasonable Accommodation

Neil Foster. Religious Freedom and Same Sex Marriage Laws: Constitutional and Other Issues